Archive for category July 2021

The Covid Meltdown of Indian Performing Arts

Posted by admin in July 2021, Past issues on July 1, 2021

By Samar Saha, Irwin, PA

Samar Saha, having hosted several artistes and organized several house concerts in his elegant home, is quite familiar with the devastating situation of Indian performing artistes in the Covid pandemic. Here are his thoughtful observations.

In a recent survey by Singapore’s Sunday Times, many respondents believed, musicians ranked among the top non-essential workers. As Covid-19 spread its tentacles across the world choking economies, claiming lives, and confining millions to their homes, music, an ‘essential’ part of our existence, became non-essential.

Musicians all over the world — particularly in India — are facing the roughest time in the pandemic. In India, its film industry and live theaters froze; light and classical music concerts and dance recitals simply vanished, affecting the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of people directly and indirectly living off these activities. Many artistes are reassessing their personal situation within the industry.

The lives of musicians have changed — the worst affected are the accompanying artistes on the tabla, violin, mridangam, ghatam, guitar, flute, sarangi… Some of the hands that created wonders on these instruments have been forced to do house painting to earn their bread. To keep their music alive, they have started on-line concerts. But to ardent fans, on-line programs are not real — no matter how we spin it.

A Burmese Pagoda, not a Hindu temple Gopuram, is a better metaphor for Indian performing arts. In Karnatic music, stars like Sudha Raghunathan are at the top of the Pagoda. The pagoda has a wide base where thousands of faceless accompanists struggle to make a living. The handful few stars at the top suck up all the money, fame, and glory.

In this pandemic, the artistes, both stars and their accompanying artistes, were forced into a deep freeze. The stars have enough savings, and many others have careers outside the arts to tide them over the rough patch; or are married to spouses having stable incomes. But the not-so-famous accompanying artistes who depend solely on their arts income are struggling. A suicide attempt by a middle-aged harmonium player in Howrah in May sent shock waves. There was no food at his home and no resources to get any.

When I talked to the Kolkata-based world-renowned sarod player, Tejen Majumdar, he told me how he himself was depressed during the lockdown: “For an accompanying artiste, without concerts, there was no work, no income, no stipend; and the savings were gone. Then there was the matter of dignity. How does an artiste of good stature, who has given so much to the world by way of his art, put out his hands and beg for money?†Majumdar continued, “When I heard that the pandemic drove the harmonium artiste towards suicide, it was difficult and painful for me to come to terms with it.â€

Stories like this also came from renowned tabla player Samir Chatterjee, who lives in New York. “I know musicians who are playing the lehra for a few hours for Rs 150. It’s a pity,†says Chatterjee. The people Chatterjee conversed with are reasonably well-known artistes playing tabla/violin/mridangam/ khanjira/harmonium, among the hundreds he knows. The details of their stories vary, but the theme is depressingly the same.

Take the 62-year-old Gurupriya Sundaresan, a vocalist for 45 years in Tiruchy, TN. He said in an interview that he was forced to go for “odd jobs like painting homes.†Others he knows are working part time as “security guards, postmen, and flower sellers,†to keep the income coming.

Performing artistes are the bulwark of the cultural history of any society, and integral to the economic and social fabric of nations. In recent months, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland have announced aid packages for their cultural sector, because they consider the arts as their national heritage. In India, so far, there has been no concerted effort in the same direction.

The zonal offices of Sangeet Natak Akademies (SNA) have reached out to some folk and tribal artistes who are registered with them. However, for artistes who are not affiliated with SNA, the situation is particularly grim. These include skilled artistes making musical instruments, nadaswaram players in temples, audiovisual technicians, instrument tuners, home-based music teachers, theatre artistes, costume designers, and make-up artistes, among others.

“Since the sector is completely disorganized, serious efforts in various directions are the need of the hour. There are hundreds of artistes who are not registered with any government body,†said Hindustani classical vocalist, Shubha Mudgal, in an interview with The Indian Express.

Covid-19 has exposed the soft underbelly of the music industry in India. The sarod artiste Tejen Majumdar is emphatic: We need a serious intervention.†Any solution — short term or long term — will require finding out: a) How big is this problem? (It is indeed big.) b) What are the short- and long-term needs? c) Can they be tackled at the local level, or will it require larger programs over longer durations?

These are the questions facing music aficionados. Some private efforts have been recently initiated. But these are limited, at best. Karnatic vocalist and Magsaysay recipient T.M.Krishna monetized one of his concerts in April to help artistes in need. He also created a fund for helping makeup artists, parai, koothu and karagattam artistes, instrument makers, nadaswaram and thavil artists, theatre artists, people working backstage and audiovisual technicians.

Talking to The Indian Express, the Hindustani classical vocalist Shubha Mudgal, who has given a recital in Pittsburgh, said, “We started discussing early on because we went through several cancellations ourselves.†Mudgal began calling artistes she knew — some living in remote places. Mudgal did not want to rush into doing a monetized concert to raise funds. She wanted to figure out if money could be raised for long-term needs because paying these artistes small amounts would only last for a short time. She got in touch with people/organizations working with musicians at the grass roots level to find artistes in desperate need.

Now many musician groups and industries related to music have joined the fray — not altruistically but for their own long-term survival. Realizing the deleterious effects of declaring performing “non-essential,†many big industrial names — like recording companies, Reliance Industries, film industries, software companies, famous and not-so famous names in Karnatic and Hindustani music and individuals — have risen to the occasion. Most realize how closely knit is this fabric of music and people at large. “While the system fails us, our leaders lead us astray and dark, morbid motivations are at work, minute by minute, kindness also pours in — citizens rally, cook, feed, care, cry, sing, mourn, make calls, help a friend, hold each other even at a distance,†cried a journalist out of sheer frustration.

This is the time for all of us to rise to the occasion. Do find out the individuals and associations genuinely involved in raising funds for the needy artistes, even on a short-term survival basis, and donate. Two organizations doing a great job for the relief of artistes are: Chhandayan of New York, and T.M.Krishna’s Crowd Funding. Here are the links for the two sites:

Samir Chatterjee’s: www.tabla.org/donate

T.M.Krishna’s: www.tinyurl.com/HelpingArtistesinPandemic

Please go to these websites and donate. Let the big organizations and the government attend to the long-term solutions. I realize that asking readers to go on-line for donation is just a band aid to this immense problem as European countries have found out. This is not a long-term solution. But we should do our bit to help artistes in distress in the pandemic. END

Home:

Indian Americans at West Virginia University

Posted by admin in July 2021, Past issues on July 1, 2021

By Mohindar S. Seehra email: mseehra707@gmail.com

Professor Emeritus, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV

Great universities are built on visionary leaderships, adequate resources, and dedicated high-quality faculty, which in turn, attract bright students. West Virginia University (WVU), a comprehensive land-grant university in Morgantown with about 30,000 students, reached the coveted Research Level-1 status in 2015 based on diversity in its doctoral programs, quality of research publications, and level of research expenditures. Last year, WVU received $195 million in research grants and contracts, and awarded 190 PhDs.

Indian Americans are only few among the faculty at WVU, but their contribution to this achievement is significant through their leadership and research work. When I started as an Assistant Professor in Physics in 1969, the other Indian faculty I met were Atam Arya (Physics); Joginder Nath and Rabinder Singh (Agri. Sciences); Satya Rochlani (Pathology); Hota Ganga Rao and Sunder Advani (Engg.); and Ranjit Majumder (Psychology).

Among later additions were Harakh Dedhia (Pulmonology); Abnash Jain (Cardiology); Ramana Reddy (Computer Sci.); Jag Jagannathan (Biochemical Pathology); Rumy Hilloowala (Anatomy); Ashok Abbott (Finance); Rakesh Gupta and Dady Dadyburjor (Chem. Engg.); Rashpal Ahluwalia (Industrial Engg); and Radhey Sharma and Nithi Sivaneri (Civil Engg.).

While all excelled in teaching and research, Drs. Jain, Dadyburjor, Gupta and Sharma also had multi-year stints as department chairs. More Indian Americans joined in recent years particularly in engineering and medicine, notably, Vinay Badhwar as Chair of the Heart & Vascular Institute; and Srinivas Palanki as Chair of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering. Rakesh Gupta, Hota GangaRao, Debangsu Bhattacharyya, Brijes Mishra, and Vinay Badhwar are now named the Distinguished Professors. I became Professor in 1977, Eberly Distinguished Professor in 1992 and retired in 2016 after 47 years of service.

The highest honor at WVU is induction into the Order of Vandalia “for Distinguished Service to the University,†given to a few select retirees, distinguished alumni, and benefactors. Since 1961, 150 individuals have received this honor, among them US Senators Robert C. Byrd in 1992 and John D. Rockefeller IV in 2009. Prof. Joginder Nath received this honor in 2016. Receiving this honor in 2019 was a fulfilling moment for me after years of struggle and hard work in my earlier years in India and after coming to the US in 1963. END

Home:

Obituary: Jayesh Selokar (1970 to April 8, 2021)

Posted by admin in July 2021, Past issues on July 1, 2021

By Shesh Arkalgud, Murrysville, PA

Jayesh Selokar, a resident of Murrysville for 10 years, passed away suddenly on April 8, 2021 in Kuwait, where he was on work. He was 51 and the cause of his death was cardiac arrest.

He was born in Rourkela, Orissa. After receiving his electrical engineering degree from Nagpur University, India, he worked at the Bhilai Steel Plant in India before moving to Dubai where he worked at the Dubai Port Authority for 7 years. Then he made his way to Canada before landing in the US.

He married Rohini in 1999, and came to Pittsburgh in 2011. Hewas with the Elliott Group untill his demise. He completed e-MBA from IUP in 2019. He leaves behind Rohini and his two sons, Harshvardhan, 21, and Aryan, 15.He was well-connected with the community through his social ventures and at the Hindu-Jain Temple’s Executive Committee and Humanitarian Committee. He was also active in the Maharashtra Mandal.

Selokar’s mortal remains were brought to Pittsburgh on April 21st and cremated at the Beinhauer Funeral Home on April 22, 2021 with Pandit Suresh Joshi from the Hindu-Jain Temple helping the Selokars with the cremation rites. END

Home:

Pittsburgh Indians Help Sending Oxygen Concentrators to India

Posted by admin in July 2021, Past issues on July 1, 2021

By Sailesh Kapadia, Wexford, PA

In early May, there was an appeal from a government hospital in New Delhi for oxygen concentrators for Covid patients. The nonprofit Wheel Global, a 501c3 organization in Washington DC, and the alumni of the Indian Institutes of Technology received the request. Wheel Global’s inspiration was the late President of India, Dr.Abdul Kalaam, who in 2006 challenged IIT alumni to solve the “big problems facing India, the United States, and the rest of the World.â€

Wheels Global, collaborating with the IIT Delhi Excellence Foundation (IITDEF), ordered from DeVilbiss Co. located in Somerset, PA, all the 434 numbers of the FDA-approved oxygen concentrators available from them at that point. IITDEF and Wheels Global arranged the funds for the product, negotiated prices, and expedited shipping/delivery post-haste.

However, to comply with customs regulations in the US and India, DeVilbiss needed to fasten government-approved labels on each unit and every pallet of 12 units, a time-consuming step.

The coordinator, Himanshu Verma, a former resident of Pittsburgh, now living in Washington DC, asked for help from Pittsburgh to complete the job so that the shipment could go out in time to get on the Air India flight to New Delhi that same day.

When apprised of this need, Jamnadas Thakkar, a long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist in our area, wanted to get this done quickly. He contacted Manoj Kansara, the Financial Manager of a motel in Somerset. Kansara readily volunteered, went to the DeVilbiss plant, and got the job done.

The units were shipped on the same day in time to New Delhi and on arrival at Delhi, were distributed to hospitals in Delhi and IIT Delhi where the remainder of the units were retained for distribution to other needy places in India. For further information visit www.wheelsglobal.org or email suresh@wheelsglobal.org. END

Home:

Spring Arrived — Summer is Here

Posted by admin in July 2021, Past issues on July 1, 2021

The Pandemic Reveals India’s Soft Underbelly

Posted by admin in July 2021, Past issues on July 1, 2021

Simply focusing on the immediate problem and blaming Modi have given the Indian intelligentsia a convenient excuse to evade the serious introspection needed to get to the root causes to fix the problem. But in an unexpected way, the harsh reality came out when Mr. Adar Poonawalla, the CEO of the Pune-based Serum Institute of India (SII), was interviewed by The Times in London in April. Poonawalla’s SII is the No 1 producer of Covid vaccine in India. SII is the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer (over 1.5 billion doses sold in 170 countries), not only for Covid-19, but also for polio, diphtheria, tetanus, and others.

Poonawalla fled to London in April 2021, when powerful people in India threatened him with dire consequences if he did not give them the Covid vaccine ahead of others in direr straits. In the interview Poonawalla said he got menacing phone calls from chief ministers of Indian states, heads of business conglomerates and others demanding instant supplies of the vaccines. This is what he told The Times:

“Threats is an understatement. The level of expectation and aggression is unprecedented, overwhelming. Everyone feels they should get the vaccine. They can’t understand why anyone else should get it before them. The calls begin cordially, but when I explain that I cannot possibly meet the callers’ demands, the conversations go in a very different direction. They are saying if you don’t give us the vaccine it’s not going to be good. It’s not foul language. It’s the tone. It’s the implication of what they might do if I don’t comply. It’s taking control, not letting us do anything unless we give in to their demands.â€

Modi’s government gave Poonawalla the highest-level security detail, but Poonawalla still felt threatened, and fled to London. His company is getting round-the-clock police protection. Poonawalla told The Times: “I’m staying here an extended time… I don’t want to be in a situation where… … you don’t want to guess what they are going to do.â€

This is how the CEO of a company making a critical life-saving drug (desperately needed by over 1 billion Indians) is threatened. You can imagine how ordinary businesses in India are harassed by local politicians subtly demanding protection monies under the guise of fundraising and by senior bureaucrats slyly seeking bribes/favors to get their jobs done. And how millions of street vendors and shop owners routinely grease the palms of local police and low-level bureaucrats to avoid harassment. Businesses matter-of-factly take these bribes as “operating costs,†passing them on to their consumers. Thus, citizens directly bear the brunt of corruption in terms of high costs, and indirectly in terms of the poor quality of products and service for everything.Â

India’s organized sector (large and midsize public and private companies, banks, healthcare, transportation, and others) sits on the loose sand of its unorganized, informal sector — daily wage earners, taxi drivers, domestic help, small farmers, vegetable vendors and millions of nano-entrepreneurs. The unorganized sector’s workers —~80% of India’s workforce — are not well-educated and are aware that most of them are not anglicized enough to ever join the organized sector. This class does not have the bonuses or other savings available to those in the organized sector.

Out of this unorganized sector emerge leaders of raw politics. Those who succeed become elected officials running local, state, and federal governments, jumping ahead of the intelligentsia in wielding raw power. Many also end up in the underworld developing a symbiotic dependence with politicians, industrialists, and India’s polyglot film industry. Consider this: over 2500 sitting members of parliament and state legislatures in India have criminal cases against them.

In this milieu, the Indian middle-class and above have nurtured their lifestyle over the last 50 years, developing a network with their socioeconomic equals and wannabes, with their myopic ideas on neighborhood and obligations to citizens at large. In India, in 2020, with 300 million people estimated to be in the middle class, only 58 million people filed income tax returns, with only 15 million actually paying income tax (www.tinyurl.com/IncomeTaxPayersIndia).

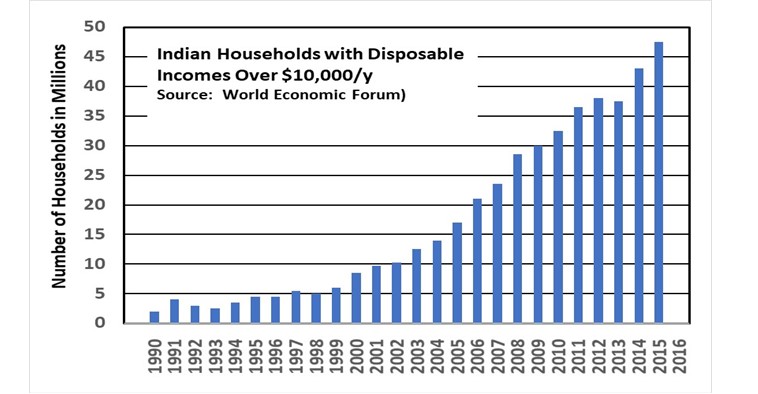

But the World Economic Forum (www.tinyurl.com/IndiaDisposableIncome) reports that even in 2015, nearly 50 million people had disposable incomes of $10,000/year (INR 750,000/year). See the plot below. With income tax levied for taxable incomes more than INR 250,000/year, Indians have perfected tax evasion. In the US, by comparison, 50% of households pay income tax.

The Indian middle class demands all kinds of service without paying for them through taxes; but it is ever ready to berate governments for the problems du jour, such as the entirely predictable annual monsoon floods; and as is now the case, the Covid pandemic.

In this milieu, the Indian middle class over the last 5 decades has developed a schizophrenic lifestyle. While physically living in affluent parts of Indian urban areas, they mentally live in Amsterdam, London, NYC, Boston, the Bay Area, Dubai, Singapore, Sydney… Like American suburbanites, they insulate themselves from, and are oblivious to, local issues where they live. Because of their access to resources, they are well-informed, often well-travelled, with a network of contacts spread across the world. This class routinely and without any hesitation gets its jobs done ahead of others through their contacts with those in power and influence, or with bribes.

And then, in the second wave of the pandemic, the metaphorical excreta hit the fan, splashing it on everybody’s face. India’s middle and affluent classes are deeply embarrassed and angry. But instead of doing some serious soul-searching on why they are where they are today, they scream at Modi’s central government, making him personally responsible. In reality, though, they have been contributing to the problems for three generations.

Educated Indians do not need any advice from outside experts to fix this problem. The Covid crisis will eventually force them to dispassionately look at themselves and reorganize their society on truly egalitarian ideas they all can agree on. They can study the models of Japan, Germany or the Scandinavian countries, where everybody pays their share of taxes for the state to provide decent education and quality preventive healthcare for all. The goal should be to give opportunities for today’s poor through education and enterprise and make them prosper to become tax paying citizens and thus help governments to pull up people below them.

They will have to abandon the laissez-faire model of unfettered free enterprise, the same way they abandoned the other extreme of the Soviet model state-controlled economy. After trying the Soviet model for 50 years, India had to abandon it when the whole nation was driven to the brink of bankruptcy in the late 1980s.

Everybody must give something to get something in return, both tangible and intangible. They do not have to look too far. They only need to go to their own traditions to learn of the mutual obligations of every segment of society to others. END

Home:

Covid-19’s Second Wave in India

Posted by admin in July 2021, Past issues on July 1, 2021

Note: The author acknowledges Arun Jatkar, Monroeville, PA; Lalit Mohan Gantayet, Navi Mumbai, India; Verghese Chandy, Melbourne, Australia; and K. Suryanarayanan, Chennai, India for their thoughtful review and suggestions on the drafts before it was finalized.

By now everyone has seen them — horrifying images of mass cremations on open grounds in newspapers, and flashed on TV screens across the globe. Gory video clips showed in blatant invasion of privacy, decency, and sensitivity, patients in trauma minutes away from death in crowded New Delhi’s ICUs. They dared not show these scenes that routinely did happen in ICUs across the US a scant ten months earlier. Denigrating India is fair game in the global media.

In April-May the second wave of the pandemic hit the Indian middle and affluent classes as well. The widely reported shortage of medical oxygen, a routine item in normal times, for Covid patients in ICUs only accentuated the issue. The polyglot voices of politicians and opinion writers in the ratings-driven Indian media understandably pinned down Prime Minister Modi, berating him for everything that went wrong.

What the Indian media, or international media, did not highlight is the lackadaisical response of state governments and the profiteering attitude of the profit-driven private hospitals that led to the oxygen shortage. Here (www.tinyurl.com/GurumurthyO2) is a story on how the shortage was precipitated by profit-driven private hospitals.

Here (www.tinyurl.com/GulfNewsOnModi) is another story discussing whether the Modi government was negligent. The drift of this article is that a) the Modi government did anticipate the second wave, and did warn state governments; b) opposition parties did not want the Modi government to ban open election rallies during the pandemic; and c) the Modi government expanded the medical infrastructure (isolation beds and ICUs) by several multiples during the pandemic. Granted, whatever was done was not adequate given the enormity of the pandemic.

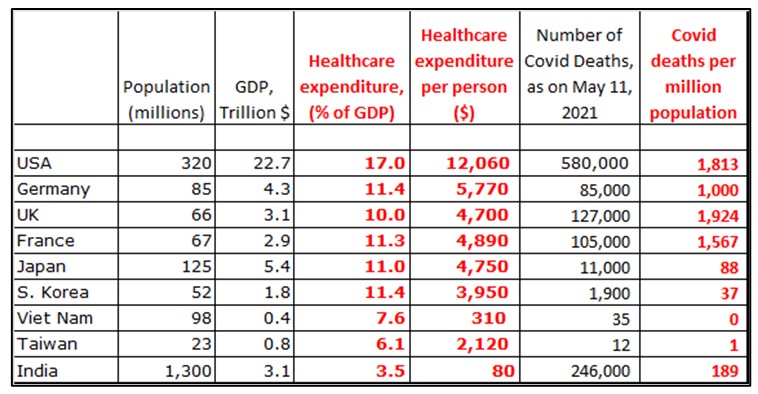

India’s pandemic crisis needs to be seen in the global context. See the table below.

Mortality Table for Select Countries (data from WHO)

• The US and the industrialized West, despite its high GDPs (column 3), high expenditure on healthcare as a % of its GDP (column 4), high per-capita healthcare expenditure (column 5), high standards of living, and far better healthcare infrastructure than the rest of the world, did poorly in managing the Covid pandemic (last column).

• Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and Vietnam, neighboring China from where the Covid pandemic originated, responded much better than the industrialized West. Compare the numbers in the last column. Vietnam is a developing economy. What did they do right that the West did not, and did we learn anything at all from them?

• In India, the officially reported mortality rate is ~200/million, even with its poor investments in healthcare (more on this later). It is quite possible that India under-reported or misclassified its mortality numbers. Even if we assume India’s actual mortality rate is twice, or thrice (that is, 100% or 200% more), it would still be ~400/million or ~600/million, not anywhere near the more than 1,800 deaths/million in the US.

• But with India’s free, confrontational media hostile to Modi, and with NGOs everywhere, deliberate large-scale suppression of Covid mortality data is not easy in India’s federal system of governance. All Covid-positive diagnoses and deaths nation-wide have to be immediately reported to the Indian Council of Medical Research that gathers and collates all raw data and keeps a close watch on this pandemic’s spread.

India’s Healthcare System:

In the Indian constitution, healthcare is a state subject with democratically elected governments driving the healthcare policies in each state. This is because of India’s demographic diversities in every metric and wide variations in available resources and priorities. With disparate political parties at loggerheads with each other running the 30-plus state governments, massive, deliberate fudging of covid mortality numbers would be difficult for the federal government.

The profit-driven Indian healthcare industry is unregulated, modeled after the American pay-per-service system (but without any oversight). Private general practitioners are at the bottom of the pyramid with specialists in the expensive super-specialty hospitals at the top.

The poor/working poor go to the inadequately funded, poorly equipped, and badly managed government hospitals for all their needs; in these hospitals, the service is free, but far from satisfactory. Government hospitals train new doctors with dedicated senior clinicians drawn by the challenges to serve the poor.

The poor cannot afford expensive pay-per-service private doctors. Consider this: tertiary medical care for a knee replacement + 2-week hospital stay costs INR 500,000 to 700,000 in a second-tier private hospital, way beyond the reach of working-class Indians earning and spending in rupees. The middle class go to private doctors and private hospitals they can afford. The rich go to the expensive super-specialty hospitals.

The Covid pandemic brought out many depressing features that have been festering for nearly six decades in India’s healthcare sector, with both omissions and commissions by different segments:

• Poor investment decisions in public health and primary care by state governments for over 70 years (Modi came to power only six years before the pandemic exploded).

• Unregulated pharmaceutical and medical supplies industry — many of them multinational companies based in the EU and the US.

• Practicing physicians owning medical labs with vested interests.

• The high cost of medical education in profit-driven private medical colleges run by politicians under the rubric of tax-exempt foundations. The cost of fees plus books and supplies in a profit-driven private medial college for a five year program exceeds INR 10,000,000 (or 1 crore rupees). To this you need to add the cost of boarding and lodging. Freshly minted doctors coming our of medical colleges with this kind of “investment” are in a great pressure to recover the money as quickly as possible.

• Low tax base for the governments (more on this later); and

• The sinister practice of unethical, illegal payments permeating the entire healthcare industry.

The last item is pernicious and needs some elaboration:

• All drug companies — European, American and Indian — bribe doctors in India for prescribing their medications on a prorated basis. The more you prescribe, the more you get as bribe.

• Specialists bribe general physicians to refer patients to them.

• Labs bribe physicians and surgeons to refer patients to their labs for blood work, pathological tests, and X-rays, CT-scans, etc.

• Hospitals bribe doctors for referring patients into their facilities.

• Often the doctors themselves own these labs, tempting them to order more tests than what are needed.

All these unethical and illegal payments are deviously transferred to patients, who often do not have health insurance and bear 100% of the cost from their own pockets. These payments can be up to 40% of the final costs. The unscrupulous ways in which India’s healthcare industry — doctors, European, America, and Indian pharmaceutical companies, hospitals and medical labs — bilks helpless patients in India are well-known.

So, the industry of healthcare delivery is predatory and exploitative throughout India. Often, the interactions are hostile between private doctors and patients (who bare 100% of the cost of the medical care out of their own pockets). This is because of the lack of trust between the doctors and the patients when it comes to the need for tests, and how much they will be charged.

Thus, the impenetrable thicket of India’s healthcare industry is sustained by a mutually exploitative dependence among all segments of the unregulated healthcare system with no oversight. This system has been ripping off the hapless patients for over 50 years. No wonder there is no incentive for preventive and primary care in Indian healthcare system. END