By Samar Saha, Irwin, PA

Samar Saha, having hosted several artistes and organized several house concerts in his elegant home, is quite familiar with the devastating situation of Indian performing artistes in the Covid pandemic. Here are his thoughtful observations.

In a recent survey by Singapore’s Sunday Times, many respondents believed, musicians ranked among the top non-essential workers. As Covid-19 spread its tentacles across the world choking economies, claiming lives, and confining millions to their homes, music, an ‘essential’ part of our existence, became non-essential.

Musicians all over the world — particularly in India — are facing the roughest time in the pandemic. In India, its film industry and live theaters froze; light and classical music concerts and dance recitals simply vanished, affecting the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of people directly and indirectly living off these activities. Many artistes are reassessing their personal situation within the industry.

The lives of musicians have changed — the worst affected are the accompanying artistes on the tabla, violin, mridangam, ghatam, guitar, flute, sarangi… Some of the hands that created wonders on these instruments have been forced to do house painting to earn their bread. To keep their music alive, they have started on-line concerts. But to ardent fans, on-line programs are not real — no matter how we spin it.

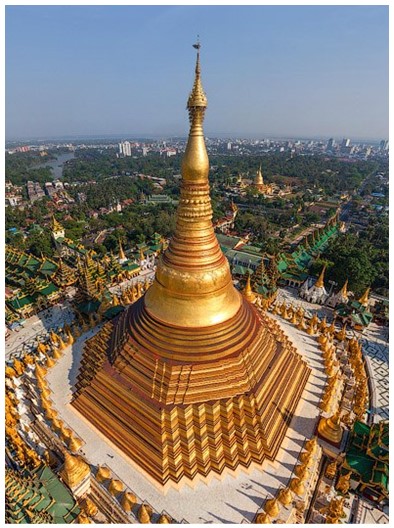

A Burmese Pagoda, not a Hindu temple Gopuram, is a better metaphor for Indian performing arts. In Karnatic music, stars like Sudha Raghunathan are at the top of the Pagoda. The pagoda has a wide base where thousands of faceless accompanists struggle to make a living. The handful few stars at the top suck up all the money, fame, and glory.

In this pandemic, the artistes, both stars and their accompanying artistes, were forced into a deep freeze. The stars have enough savings, and many others have careers outside the arts to tide them over the rough patch; or are married to spouses having stable incomes. But the not-so-famous accompanying artistes who depend solely on their arts income are struggling. A suicide attempt by a middle-aged harmonium player in Howrah in May sent shock waves. There was no food at his home and no resources to get any.

When I talked to the Kolkata-based world-renowned sarod player, Tejen Majumdar, he told me how he himself was depressed during the lockdown: “For an accompanying artiste, without concerts, there was no work, no income, no stipend; and the savings were gone. Then there was the matter of dignity. How does an artiste of good stature, who has given so much to the world by way of his art, put out his hands and beg for money?†Majumdar continued, “When I heard that the pandemic drove the harmonium artiste towards suicide, it was difficult and painful for me to come to terms with it.â€

Stories like this also came from renowned tabla player Samir Chatterjee, who lives in New York. “I know musicians who are playing the lehra for a few hours for Rs 150. It’s a pity,†says Chatterjee. The people Chatterjee conversed with are reasonably well-known artistes playing tabla/violin/mridangam/ khanjira/harmonium, among the hundreds he knows. The details of their stories vary, but the theme is depressingly the same.

Take the 62-year-old Gurupriya Sundaresan, a vocalist for 45 years in Tiruchy, TN. He said in an interview that he was forced to go for “odd jobs like painting homes.†Others he knows are working part time as “security guards, postmen, and flower sellers,†to keep the income coming.

Performing artistes are the bulwark of the cultural history of any society, and integral to the economic and social fabric of nations. In recent months, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland have announced aid packages for their cultural sector, because they consider the arts as their national heritage. In India, so far, there has been no concerted effort in the same direction.

The zonal offices of Sangeet Natak Akademies (SNA) have reached out to some folk and tribal artistes who are registered with them. However, for artistes who are not affiliated with SNA, the situation is particularly grim. These include skilled artistes making musical instruments, nadaswaram players in temples, audiovisual technicians, instrument tuners, home-based music teachers, theatre artistes, costume designers, and make-up artistes, among others.

“Since the sector is completely disorganized, serious efforts in various directions are the need of the hour. There are hundreds of artistes who are not registered with any government body,†said Hindustani classical vocalist, Shubha Mudgal, in an interview with The Indian Express.

Covid-19 has exposed the soft underbelly of the music industry in India. The sarod artiste Tejen Majumdar is emphatic: We need a serious intervention.†Any solution — short term or long term — will require finding out: a) How big is this problem? (It is indeed big.) b) What are the short- and long-term needs? c) Can they be tackled at the local level, or will it require larger programs over longer durations?

These are the questions facing music aficionados. Some private efforts have been recently initiated. But these are limited, at best. Karnatic vocalist and Magsaysay recipient T.M.Krishna monetized one of his concerts in April to help artistes in need. He also created a fund for helping makeup artists, parai, koothu and karagattam artistes, instrument makers, nadaswaram and thavil artists, theatre artists, people working backstage and audiovisual technicians.

Talking to The Indian Express, the Hindustani classical vocalist Shubha Mudgal, who has given a recital in Pittsburgh, said, “We started discussing early on because we went through several cancellations ourselves.†Mudgal began calling artistes she knew — some living in remote places. Mudgal did not want to rush into doing a monetized concert to raise funds. She wanted to figure out if money could be raised for long-term needs because paying these artistes small amounts would only last for a short time. She got in touch with people/organizations working with musicians at the grass roots level to find artistes in desperate need.

Now many musician groups and industries related to music have joined the fray — not altruistically but for their own long-term survival. Realizing the deleterious effects of declaring performing “non-essential,†many big industrial names — like recording companies, Reliance Industries, film industries, software companies, famous and not-so famous names in Karnatic and Hindustani music and individuals — have risen to the occasion. Most realize how closely knit is this fabric of music and people at large. “While the system fails us, our leaders lead us astray and dark, morbid motivations are at work, minute by minute, kindness also pours in — citizens rally, cook, feed, care, cry, sing, mourn, make calls, help a friend, hold each other even at a distance,†cried a journalist out of sheer frustration.

This is the time for all of us to rise to the occasion. Do find out the individuals and associations genuinely involved in raising funds for the needy artistes, even on a short-term survival basis, and donate. Two organizations doing a great job for the relief of artistes are: Chhandayan of New York, and T.M.Krishna’s Crowd Funding. Here are the links for the two sites:

Samir Chatterjee’s: www.tabla.org/donate

T.M.Krishna’s: www.tinyurl.com/HelpingArtistesinPandemic

Please go to these websites and donate. Let the big organizations and the government attend to the long-term solutions. I realize that asking readers to go on-line for donation is just a band aid to this immense problem as European countries have found out. This is not a long-term solution. But we should do our bit to help artistes in distress in the pandemic. END