Archive for category April 2011

Shining India Does not Shine for a Whole Lot

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

I was in India for nearly six weeks early this year mostly in Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu, a second tier Indian city with a long history of natural enterprise built without too much support from either federal or state government. In and around Coimbatore, you need to drill deeper than 300’ to get water, and still, you see small-scale farming all around. That is how enterprising people there are.

The economic, social, and cultural impact of old-time established enterprising social groups — the Naidus, Gounders, and Chettiars, and others — is everywhere in Coimbatore. They prime the economy of the region. In addition, their well-known philanthropic institutions are scattered all over the city in primary and secondary education, and in all branches of higher education in the sciences, liberal arts, management, engineering & technology and healthcare. Gujaratis, Marwaris and Keralites in the last 30 to 40 years are recent entrants. But they are mostly only in trade abd business.

In the main shopping streets most of the signage for shops are only in the Roman script. Only rarely the boards are in Tamil. In the only small newspaper/bookstore at the small Coimbatore airport, not even one Tamil magazine or newspaper is on display. Only US publications or India’s English dailies/weeklies. What Macaulay and the British could not accomplish in their 150 years of Indian occupation, Indians themselves have done in sixty-four years since independence.

Multi-storey apartment complexes are fast replacing single-family houses in coimbatore and in many other second-tier towns. Four- to 6-storey apartment complexes with 16 to 24 apartments with up to 1500 sq. foot living area are fast replacing single-family homes. Nobody seems to worry about the bad societal and public health consequences on the population density going up 20 times with the same infrastructure intended for a much smaller population density.

The affluent live in expansive gated villas in luxurious lifestyles, including separate housemaids for cooking and cleaning. The villas look like haciendas in the Southwest. But when you step outside, the familiar Old India (which has become only worse) stares at you: Dusty roads with potholes; open sewers; maddening traffic with buses, trucks, vans, cars, motorbikes, scooters, and bikes all using the same lanes; with everybody blowing horns and nobody caring for traffic rules; water and air pollution; garbage piling up with plastics strewn all over the place… …

Another trend in places like Coimbatore, Mysore, Nashik is relatively affluent retirees from other places settling down in exclusive old-age communities. Their children live far away in India or overseas. This structural change in family arrangement has far-reaching social implications for India.

In Coimbatore bakeries are everywhere selling rich cakes and cookies in addition to halvas, jilebis, jangris, and a variety of deep-fried savories — all bad for your cardiovascular and endocrine systems. With a large section of the population having become sedentary and affluent, not surprisingly, in between the bakeries you see pharmacies and doctors’ offices specializing in heart diseases and diabetes.

People in India overwhelmingly seek English-medium private schools for their children. Some of the schools, such as the International Boarding Schools are for the really affluent, cost a fortune – several hundred thousand rupees per year. Even ordinary private high schools run into several tens of thousands of rupees per year. College education too is prohibitively expensive, in hundreds thousand rupees per year, way beyond the reach of the bottom half of the population.

Elective surgery is big business in Coimbatore. Some of the private hospitals for orthopedic and cardiac care are well known in many parts of India. For people with their own resources, these hospitals offer affordable care compared to what costs in Mumbai or Chennai. Patients come from all over India, and even from neighboring countries.

I went to a well-kept eyecare clinic where my mother had cataract done. The place was overflowing with hospital staff. Upon discharge, they send you home with flowers and fruits. The outpatient cataract removal for one eye costs around Rs. 30,000, a significant amount in the absence of medical insurance for working-class Indians earning in rupees and spending in rupees. This is way out of reach for nearly 75% of the population.

With no medical insurance for large sections of the population, which is unaffordable even when available, and no equivalent of Medicare for the elderly or Medicaid for the indegent, 100% of the hospital expense in private hospitals is out-of-pocket.

The unregulated private-sector-driven healthcare industry has retained the worst of India’s native healthcare practices and superimposed on it some of the worst US medical practices. While this serves the interests of the Indian healthcare industryy extremely well, this is the worst arrangement for patients needing care with limited resources like the working-class framilies earning in rupees and spenging in rupees.

It is common for physicians ordering tests – blood work, echocardiogram, and scans and others – to get commissions — they can be also called kickbacks –  up to 30% of what the labs charge the patients from the labs for ordering the tests. Specialists give commissions for GPs (general practitioners) for referring patients to them. And doctors get kickbacks from hospitals for admitting patients into their facilities.

Not surprisingly, often the interactions between the patients and their doctors become testy when they order more tests or refer them to more specialists since 100% of the costs of the tests are borne by the patients. I personally know many families that called themselves “middle class†only a few years ago, now staring at bankruptcy on account of unmanageable healthcare cost in senior years.

The conditions in, and the resources of, the government hospitals are so bad that they are only meant for the abjectly poor.Â

We constantly read about India’s 9% and 10% growth rates in business magazines and anecdotal stories on India Shining: McDonalds and KFCs in urban centers, shopping malls coming all over, fashion shows with emaciated models swinging down the catwalks, auto dealership for BMW, Saabs and Porches, obscenely extravagent weddings, showrooms of upscale European fashion merchandise… …

But these stories gloss over serious underlying structural problems in the ever-widening socioeconomic inequities among people with and without access to resources, bad infrastructure, the poor quality in education and basic healthcare for the disadvantaged, and massive corruption at every level in government.

Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, the two states with phenomenal economic growth in the last 20 years, are also states where corruption is widespread and rampant.

The Indian elite is well aware of this even though it does not want to acknowledge this in public. It is no wonder that affluent and powerful Indians – and this includes many politicians – in large numbers have bank accounts valued at hundreds of billions of $s in Switzerland, London, Singapore, and Persian Gulf Sultanates.

And notwithstanding India Shining, even the most powerful and the upper crust sections of India still want to educate their kids in the West, even as they are proud of their fancy English medium schools, IIMs, IITs, their Med Schools, their IT prowess, and even as they assert in conversations that Indians are no more enamored of the West.

In earlier centuries, only the poor Indians in large numbers migrated out trying to eke out a living to countries such as Malaysia (to sweat it out in rubber plantation), the Caribbean and Suriname (as indentured workers in the sugarcane fields), to South Africa (as poor workers), to England to work as cab drivers and bus conductors, and recently to the Persian Gulf countries (as hardworking blue-collar workers working and living in subhuman conditions).Â

A relatively recent trend now in India is that sons and daughters of a large number of India’s ruling elite — powerful politicians, senior bureaucrats, military officers, high court judges, and others belonging to the upper economic classes — have migrated to Europe, North America, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand. India’s Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s daughter, for example, works in US State Department as an attorney.

As news stories reported in The Hindu and the New York Times, sons and daughters of midlevel bureaucrats and military officers are given admissions with scholarships in US universities under circumstances that give room for a lot of suspicion.

One wonders how the decisions of India’s elected officials, senior bureaucrats and business managers will not be clouded by their filial affiliations, especially when they are widespread.

Notwithstanding the stories of Shining India in the Indian and global media, these trends suggest that at a visceral level, among India’s ruling elite there is a lurking suspicion, if not fear, that what the Shining India hides is not quite reassuring to their own long-term self-preservation in India.

Interfaith Dialog Needs to Go Beyond Tolerance

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

By Rajiv Malhotra e-mail: rajivmalhotra2007@gmail.com

Rajiv Malhotra is an author and the founder of Infinity Foundation (www.infinityfoundation.com). He is also a former telecommuncation entrepreneur. After a career in the software, computer, and telecom industries Malhotra took an early retirement to pursue philanthropic and educational activities. In 1995 he founded the Infinity Foundation, an organization based in New Jersey promoting Indic studies. The foundation defines Indic traditions to include Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, Hinduism. The following article, first appeared in the Huffington Post last year, is printed here with the author’s permission.

It is fashionable in interfaith discussions to advocate “tolerance” for other faiths. But we would find it patronizing, even downright insulting, to be “tolerated” at someone’s dinner table. No spouse would appreciate being told that his or her presence at home was being “tolerated.” No self-respecting worker accepts mere tolerance from colleagues. We tolerate those we consider inferior. In religious circles, tolerance, at best, is what the pious extend toward people they regard as heathens, idol worshippers or infidels. It is time we did away with tolerance and replaced it with “mutual respect.”

Religious tolerance was advocated in Europe after centuries of wars between opposing denominations of Christianity, each claiming to be “the one true church” and persecuting followers of “false religions.” Tolerance was a political “deal” arranged between enemies to quell the violence (a kind of cease-fire) without yielding any ground. Since it was not based on genuine respect for difference, it inevitably broke down.

My campaign against mere tolerance started in the late 1990s when I was invited to speak at a major interfaith initiative at Claremont Graduate University. Leaders of major faiths had gathered to propose a proclamation of “religious tolerance.” I argued that the word “tolerance” should be replaced with “mutual respect” in the resolution. The following day, Professor Karen Jo Torjesen, the organizer and head of religious studies at Claremont, told me I had caused a “sensation.” Not everyone present could easily accept such a radical idea, she said, but added that she herself was in agreement. Clearly, I had hit a raw nerve.

I then decided to experiment with “mutual respect†as a replacement for the oft-touted “tolerance” in my forthcoming talks and lectures. I found that while most practitioners of dharma religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism) readily espouse mutual respect, there is considerable resistance from the Abrahamic faiths.

Soon afterwards, at the United Nation’s Millennium Religion Summit in 2000, the Hindu delegation led by Swami Dayananda Saraswati insisted that in the official draft the term “tolerance” be replaced with “utual respect.” Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict), who led the Vatican delegation, strongly objected to this. After all, if religions deemed “heathen” were to be officially respected, there would be no justification for converting their adherents to Christianity.

The matter reached a critical stage and some serious fighting erupted. The Hindu side held firm that the time had come for the non-Abrahamic religions to be formally respected as equals at the table and not just tolerated by the Abrahamic religions. At the very last minute, the Vatican blinked and the final resolution did call for “mutual respect.” However, within a month, the Vatican issued a new policy stating that while “followers of other religions can receive divine grace, it is also certain that objectively speaking they are in a gravely deficient situation in comparison with those who, in the Church, have the fullness of the means of salvation.” Many liberal Christians condemned this policy, yet it remains the Vatican’s official position.

My experiments in proposing mutual respect have also involved liberal Muslims. Soon after Sept. 11, 2001, in a radio interview in Dallas, I explained why mutual respect among religions is better than tolerance. One caller, identified as a local Pakistani community leader, congratulated me and expressed complete agreement. For her benefit, I elaborated that in Hinduism we frequently worship images of the divine, may view the divine as feminine, and that we believe in reincarnation. I felt glad that she had agreed to respect all this, and I clarified that “mutual respect” merely means that I am respected for my faith, with no requirement for others to adopt or practice it. I wanted to make sure she knew what she had agreed to respect and wasn’t merely being politically correct. The woman hung up.

In 2007, I was invited to an event in Delhi where a visiting delegation from Emory University was promoting their newly formed Inter-Religious Council as a vehicle to achieve religious harmony. In attendance was Emory’s Dean of the Chapel and Religious Life, who happens to be an ordained Lutheran minister. I asked her if her work on the Inter-Religious Council was consistent and compatible with her preaching as a Lutheran minister, and she confidently replied that it was. I then asked: “Is it Lutheran doctrine merely to ‘tolerate’ other religions or also to respect them, and by respect I mean acknowledging them as legitimate religions and equally valid paths to God”? She replied that this was “an important question,” one that she had been “thinking about,” but that there are “no easy answers.”

It is disingenuous for any faith leader to preach one thing to her flock while representing something contradictory to naive outsiders. The idea of “mutual respect” poses a real challenge to Christianity, which insists that salvation is only possible by grace transmitted exclusively through Jesus. Indeed, Lutheran teaching stresses this exclusivity! These formal teachings of the church would make it impossible for the Dean to respect Hinduism, as opposed to tolerating it.

Unwilling to settle for ambiguity, I continued with my questions: “As a Lutheran minister, how do you perceive Hindu murtis (sacred images)? Are there not official injunctions in your teachings against such images?” “Do you consider Krishna and Shiva to be valid manifestations of God or are they among the ‘false gods'”?

How do you see the Hindu Goddess in light of the church’s claim that God is masculine?The Dean deftly evaded every one of these questions.

Haag explained that the Latin origin of “tolerance” refers to enduring and does not convey mutual affirmation or support: “[The term] also implicitly suggests an imbalance of power in the relationship, with one of the parties in the position of giving or withholding permission for the other to be.” The Latin word for respect, by contrast, “presupposes we are equally worthy of honor. There is no room for arrogance and exclusivity in mutual respect.”

Only a minority of Christians agree with the idea of mutual respect while fully understanding what it entails. One such person is Janet Haag, editor of Sacred Journey, a Princeton-based multi-faith journal. In 2008, when I asked her my favorite question “What is your policy on pluralism?” she gave the predictable response: “We tolerate other religions.” This prompted me to explain mutual respect in Hinduism wherein each individual has the freedom to select his own personal deity (ishta-devata, not to be confused with polytheism) and pursue a highly individualized spiritual path (sva-dharma). Rather than becoming defensive or evasive, she explored this theme in her editorial in the next issue:

““”In the course of our conversation about effective interfaith dialog, [Rajiv Malhotra] pointed out that we fall short in our efforts to promote true peace and understanding in this world when we settle for tolerance instead of making the paradigm shift to mutual respect. His remarks made me think a little more deeply about the distinctiveness between the words ‘tolerance” and ‘respect,’ and the values they represent.”

Obituary: J Badri Narayan — Metallurgical Engineer with a Distinguished Career

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

by Sam Palusamy, Murrysville, PA.     e-mail: pshopp2700@yahoo.com

With great sadness, I record the sudden death of J Badri Narayan, my friend and a long-time resident in the Pittsburgh area, due to cardiac arrest. He died on Thursday, March 3, 2011 while working out on treadmill when he suddenly collapsed and fell down.

With great sadness, I record the sudden death of J Badri Narayan, my friend and a long-time resident in the Pittsburgh area, due to cardiac arrest. He died on Thursday, March 3, 2011 while working out on treadmill when he suddenly collapsed and fell down.

Born in Chennai, India, Badri was schooled in the Ramakrishna Mission School, and later earned his BS in physics in 1962 from the University of Madras through Loyola College, Chennai.

After briefly working in Bangalore, Badri came to Detroit to pursue his engineering education in Wayne State University where he received BS and MS degrees in metallurgy in 1969.

After working at Wolverine Tube, Inc., Dearborn, Michigan for two years, he joined Westinghouse Electric Company as Product Assurance Engineer in the Specialty Metals Plant (SMP), located in Blairsville, PA. His entire professional career was with Westinghouse, where he advan-ced to the rank of Fellow Engineer, a coveted title. At the time of his death, he was working as a project manager for the company’s Nuclear Fuels Division in Korea.

Badri was a key player in the early days of SMP as it transitioned from Inconel (an alloy of nickel, chromium, iron, molybdenum and other elements) to Zircaloy (based on zirconium with small amounts of tin and niobium) for making tubes needed for power generation.

During his final years spanning his 39-year career, Badri, highly respected both by his customers and peers, played a key role in successfully developing the Westinghouse Asia Fuel Business. He worked with customers all over the world, but his main role was serving customers in Korea and Japan.

In 2003, in recognition of his exceptional technical contribution to the international zirconium standards community, the International Committee of the American Society for Testing Materials (ASTM) honored Badri with the Award of Merit and the honorary title of Fellow for his distinguished service for 30 years to the ASTM.

Outside of his love for work, Badri was interested in music, theater; and enjoyed walking the dogs in parks in and around Pittsburgh, and volunteering at Sri Venkateswara Temple. He also served as president of the Delmont Lions Club.

Funeral ceremonies for Badri were held on Saturday, March 5, 2011 at Bash-Nied Funeral Home, Delmont. Badri’s son Manu performed the Hindu cremation rites for his father at St Clair Cemetery Crematorium, Greensburg with help from Shri Gopala Bhattar of S.V.Temple.

Later, in a memorial service on Sunday, March 20, 2011at Sri Venkateswara Temple, a large number of friends and acquaintances gathered reminiscing their interactions with Badri, recalling his helpful nature and his unperturbed and balanced approach to life.

Badri is survived by his beloved wife, Vatsala, and his son, Manu, a well-known singer and actor.

Why I Took the Accent Reduction Training

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

About a year ago, I started some professional training that surprised some of my Indian friends and colleagues. I started working with a coach, Judy Tobe of Claro Accent Reduction, to help me speak English with more of a neutral accent

I was born and raised in Bangalore, and I have been studying English since I was a kid. I also speak the mother tongue, Kannada.

In 2003, when I was 21 years old, I moved to the United States to earn a master’s degree in computer science from Old Dominion University in Virginia.

Three years later, I moved to Pittsburgh to accept a job with Ciber as a software engineer. In 2009, I started working at TeleTracking Technologies, a health care software company that employs about 170 people.

I work as a project manager. I manage software projects. I plan the project out, I decide what resources we need to procure, break down the project into smaller tasks, assign those tasks to other developers, and monitor progress. I make sure all the developers are doing what they are supposed to do. I manage a team of 20 people and about 40% are native English speakers. The others moved her from India, Mexico and Europe. In my role as a manager I interact with the rest of the company as well – and 100 percent of these employees are native speakers.

In Indian English, the stress on the words is on different syllables and this can make it difficult for a native English speaker to understand.

When I spelled my name on the phone, I used to have to say “P for Paris, R for Richard,†and so on. Sometimes when I spoke, people would say, “What? Can you please repeat it?â€

I thought to myself, “I have to improve my speaking.â€

A lot of people with a thick accent may not want to acknowledge that this is a problem, or feel that to change it would somehow not be true to their native culture. But for me, I thought it was a part of my communication. When you speak to people they should be able to understand you easily, especially if you are making a career in this country.

In a professional setting too, an accent can be seen as a handicap, and you have to find a way to overcome it. However, there is only so much you can overcome on your own.

In my job as a manager, I have to interact with managers from other companies and other teams. I cannot expect to do my job while speaking with an accent so strong that other people can’t understand very easily—it’s not possible.

I decided to look for professional help on this matter.I had seen a flier promoting accent reduction workshops, led by Judy Tobe, the principal of Claro Accent Reduction. I looked her up online and gave her a call.

Judy has been a speech pathologist for almost 30 years, helping people with communication. Using web-based meetings, she helps people all over the world who want to speak English with an American accent. She specializes in helping people with Indian accents and a big part of her clientele is Indian.

We did a one-hour assessment of my speech and she gave me some pointers based on the areas for improvement. Later, in April 2010, I called her back and said I wanted to work with her. We scheduled weekly sessions and she tried to help me with my pronunciation.

We started by meeting face-to-face for nearly four months. We met every Tuesday for the a few months. After that, we moved our meetings to Skype and continued our meetings on the internet. We still meet once a month online.

I am very happy with the results. I have noticed that the number of times people say “what?†to me has decreased.

Some of my friends knew I was getting help form Judy and they said “I notice that your ‘w’ and ‘th’ are different now.â€

Same with the “r†sound. It is still a still a little rough but it’s better.

I no longer need to spell my name phonetically over the phone.

In December, Judy and I were featured in a Post-Gazette article. It ran on the front page of the Sunday Business section, and I received positive feedback from many people who saw it.

Some may wonder how much these sessions cost. This will cost you a fraction of what you would spend on college.

If anyone asked me about this training, I would recommend it. I think it’s very important to speak English with more of a neutral accent, especially if you want to make a career in this country.

Indian Women: Profiles in Courage

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

India’s popular print media, particularly the English media, often stereotypes Indian women as ones who are voiceless and cowed by tradition. In these narratives, profiles of strong Indian women who often prefer to live in obscurity are rarely presented. I am in no way refuting that many Indian women struggle in their traditional roles. However, for those of us raised in India, we have all seen traditional women rooted in their families, strong in spirit and fountainheads of courage pulling their families out of rough patches in life. Often, they are respected in their communities for their grit and strength.

In the news late last year in UK was inspiring stories about two remarkable Indian women whose life trajectory just knocked me over. Both immigrants to the UK, minimally educated in the formal sense, but wise, strong-willed and rooted in their values, they changed the course of their lives and left their imprints on the fabric of Indian immigrants in the UK.

Here are profiles of these Indian women who struggled and succeeded against heavy odds in unfamiliar places, even as they retained their cultural identities.

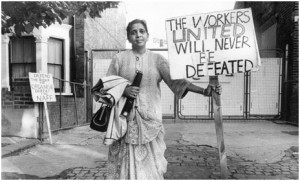

One was Shanta Gaury Pathak, cofounder of the biggest Asianpackaged food company in Britain with the Patak brand name; and the other was Jayaben Desai, inspirational leader of the Grunwick strike who fought relentlessly for respect for Indian immigrant workers from Africa, mostly women. Both died towards the end of 2010 and their obits from UK print media is the source of this article.

One was Shanta Gaury Pathak, cofounder of the biggest Asianpackaged food company in Britain with the Patak brand name; and the other was Jayaben Desai, inspirational leader of the Grunwick strike who fought relentlessly for respect for Indian immigrant workers from Africa, mostly women. Both died towards the end of 2010 and their obits from UK print media is the source of this article.

Shanta Gaury Pathak, the UK’s Curry Queen as the UK media called her, was born in Gujarat, India, moved to Kenya, and later to the UK, after the Kenyan uprising against Indians in the 1950s. She arrived with six children and five British pounds and speaking very little English.

Mortified by the idea of her husband Laxmishanker working as a drain cleaner, she started bottling and packing pickles, spices, and curries at her kitchen table. The recipes were her own, perfected through generations, rooted in her Gujarati cuisine. With her talent for cooking and her husband’s business acumen, they soon started a small shop. When 50,000 Asians arrived in UK after Uganda’s Idi Amin expelled them, her company, Patak’s, bid on a contract to supply food to the refugee camps. Later, as the refugee community settled down, and the Indian curries went mainstream in UK, Patak’s was employing over 500 people in their processing plant. Her bottled spices, curry paste, and pickles dominated the UK and European and the US market. She was the one who named the company Patak — an easier and simpler version of her own family name Pathak. After recovering from near bankruptcies twice because of business decisions, when she sold her company, her brand was worth 105 million British pounds. A devout Hindu and a traditional Gujarati, she was also active in many charitable works.

The other was Jayaben Desai. On her death, The Guardian wrote,“…She defied stereotyping all her life.†Also born in Gujarat, she wed Suryakant and settled in Tanzania, where he was a tyre factory manager, used to a comfortable lifestyle. But when they were expelled from Tanzania on its independence, she arrived in the UK, penniless.

The other was Jayaben Desai. On her death, The Guardian wrote,“…She defied stereotyping all her life.†Also born in Gujarat, she wed Suryakant and settled in Tanzania, where he was a tyre factory manager, used to a comfortable lifestyle. But when they were expelled from Tanzania on its independence, she arrived in the UK, penniless.

Her husband worked as an unskilled laborer and she took a job as a seamstress in a sweatshop. Later she went to work for an Anglo-Indian-owned mail-order film processing plant in London. Angry at the low pay and miserable working conditions for a group of immigrant women, she led a walkout of the company in a strike.

The 4’10″ Jayaben remonstrated with her 6’-plus manager, “What you are running is not a factory — it is a zoo. But in a zoo there are many types of animals. Some are monkeys that dance on your fingertips. Others are lions who can bite your head off. We are those lions, Mr. Manager.â€

The strike dragged on and they were arrested on Women’s Support Day and her cause got the nation’s outrage, eventually getting them union recognition. Even though her cause did not win in court, her efforts led to better wages and working conditions for workers. She told the final meeting, “We have shown that workers like us new to these shores will never accept being treated without dignity or respect. We have shown that white workers will support us.â€

Many of us have encountered Shanta Gaury Pathaks and Jayaben Desais in our families and communities. These family matriarchs are proof that feminism is not a foreign import to India. When circumstances demand, they rise to the occasion, despite the burden of tradition and lack of formal schooling, forging new paths for family, community and society.

“Advances in Digital Technology to Change Lifestyle in the Years Aheadâ€

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

Raghav Khanna, who grew up in Allentown, PA, is a graduate student in EE at University of Pittsburgh. Here he summarizes a recent meeting organized by Triveni International at Carnegie Mellon U.

In a meeting organized by Triveni International Club, a Pittsburgh organization for promoting cultural and social interactions among South Asians, professors working on the different facets of digital technology and engineering education at Carnegie Mellon University shared their insights on the changes ahead in the coming decades.Â

L to R Dr. Ramayya Krishnan, Dr. Juginder Luthra, Dr. Raj Reddy, Dr. Praful Desai, Dr. Pradeep Khosla. Photo by Mr. Vivian Lee of the Computer Science Department.

Prof. Raj Reddy, a member of Triveni, with his illustrious accomplishments on robotics research at the university, summarized the session thus:“The impact of the [IT-driven] technological changes in the next thirty years will be larger than the changes in the last 100 years.â€Â Dr. Reddy is the University Professor in Computer Science and Robotics at CMU.

Â

After Dr. Reddy’s brief welcoming remarks, Prof. Ramayya Krishnan, the Dean of Heinz School of Public Policy and Management, spoke on the interdisciplinary field of human behavior in information technology (IT) environments. The thesis of his research is to address the question, “How does one quantify the probability of being compromised with all kinds of personal information of people now available in the digital world?â€Â Given the proliferation of online social media and networks and the personalization of computers, many bits of of our personal information, including what we buy, where we buy, our reading preferences, and many other details — not to speak of our Social Security #s, Bank Account #s — are in the open. So protecting the privacy and confidentiality of these data is a fertile field for research.

Dr. Pradeep Khosla, the Dean of the College of Engineering, spoke next, informing about CMU’s innovative approaches for furthering engineering education globally. The resources crises around energy and water, he said, will have severe ramifications on generations to come, if scientists do not begin solving the problem now, piece by piece. Dr. Khosla highlighted CMU’s quest as a world-class academic institution to disseminate its influence to the rest of the world by citing the details of CMU’s undergraduate engineering programs in Rwanda and India.

Finally, Dr. Reddy spoke of his major accomplishments, one being the founding of Rajiv Gandhi University in India, an institution dedicated to enrolling exclusively the top-performing students from rural and economically disadvantaged background in Andhra Pradesh, India. All the needs of the students — housing, food, clothes, books and fees – are fully paid. Dr. Reddy also highlighted the challenges in providing a permanent footing to the program. Another of Dr. Reddy’s major achievement is the on-line University Digital Library System with over a million books globally accessible recently implemented .

Dr. Juginder Luthra of Triveni thanked the speakers for sharing with the audience their seminal work, and the audience for their presence on a Sunday morning. CMU provided a very Indian luncheon.

Pitt’s Nrityamala Wins in Competition

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

By Sushma Kola and Indrani Kar, University of Pittsburgh, PA

As Pitt students and veteran members of Nrityamala (founded 2006), the only student organization in the area dedicated to Indian classical dances, we are pleased that Nrityamala won 1st place at Laasya 2011 competitive event. Each year, we choreograph our own pieces to selected music. This year, the team comprised of nine post-arangetram dancers in Bharatanatyam or Kuchipudi. Shobhitha Ravi, a senior, has been captain of Nrityamala for the past two years.

L to R Standing Swarna Sunkara, Santhiya Mahikanthan, Indrani Kar, Shobhitha Ravi, Pranathi Kaki, and Sudha Mokkapati. Sitting Sushma Kola, Shipra Kumar, and Anita Rao.

The team competed at Laasya 2011 hosted by the University of Maryland on February 26th, where they walked away champions. Laasya is the only collegiate Indian classical dance competition on the East Coast, and eight teams are selected to perform following review of their audition video. The winning team gets to host the competition the following year, and Nrityamala is honored and looks forward to welcome teams from across the country to Laasya 2012 in Pittsburgh.

Pitt’s Nrityamala strives to keep the classical tradition alive by consistently performing at cultural shows on campus. This past November, they were thrilled to perform off campus for the first time at Johns Hopkins University for the classical exhibition show Nritya Mala 2010.

After humble beginnings, we have grown into a widely recognized collegiate dance team. We are excited to host Laasya 2012 and invite the Pittsburgh community to be on the lookout for Laasya promotional events. Finally, we would like to thank our respective Gurus from across the nation who have taught us so much not only in dance, but also in dedication and discipline.

Long Live Desi!

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

Many people have told me in my interactions that they do not quite like me using the term desi to refer to ourselves. None of them mean ill, and with some, I have decades of interactions. I’ve ruminated over this for quite sometime now.Â

The expressions we use in identifying ourselves or any group of people, should be appropriate to the time, place and context of the usage. One example: In a racially charged environment in the US, over time, the term to refer to people of African heritage has morphed from Negroes, Africans, Afro-Americans, Blacks, and now African-Americans.Â

Even in India, Harijan (literally God’s People), the term first used by Mohandas Gandhi for referring to India’s untouchables, has now frowned upon by the very people whom it refers to. Their chosen term now for referring to themselves, and accepted by all others, is Dalit, meaning “the Oppressed.†Incidentally, both Harijan and Dalit are etymologically rooted in Sanskrit.

With the Dalits in India guaranteed constitutional protection and preferences, which translates into raw political power, the term “untouchable†may even re-emerge with an uppercase “Untouchable†with a new nuanced meaning: When nobody in Old India would touch the “untouchable,†in the New India, now nobody will dare to touch the new “Untouchable,†in anycase, the politically well-connected ones.

In formal settings, we refer to ourselves as Indian-Americans, and the US mainstream has adapted this term. The US census Bureau, however, refers to us as Asian-Indians. India’s babus (bureaucrats) have come up with these monstrosities: NRIs (non-Resident Indians), POI (People of Indian origin), and CIOs (Citizens of Indian Origin). Now our ethnic identity is reduced to acronyms.Â

When we are communicating among ourselves on the pulp or over the airwaves, I find nothing offensive or condescending in calling ourselves desis. In fact, the word is just perfect, precise, and succinct. I do not think anybody can come up with a better term.

First, Desi is rooted in Sanskrit. With Desh meaning country, Deshi becomes an adjective and a proper noun for refering to people belonging to a Desh. People of Bangladesh refer to themselves as Bangladeshis. Videshi and Swadeshi are authentic Sanskrit adjectives meaning foreign and indigenous.

And Deshi colloquially morphed into Desi, much the same way Indra morphed into Inder in Northern and Western India. Dharmendra is Dharmeder and I.K.Gujral is Inder Kumar Gujral, and Satya morphing into Sachcha. Pardesi colloquially means a stranger or an outsider.

The term Desi entered the middleclass conversational lexicon in Bombay and New Delhi in the 1950s and 60s when large numbers of people from rural India moved to the cities seeking their livelihood, mostly in low-level, mostly muscular, brawny jobs.

The employer (seth) will be looking for additional hands, and he will tell his people that he needs “good†hands to work in the plant. And the news will percolate down among the workers, and one of them, who the owner likes, will bring his buddy from his gaum (village) to the boss telling him that “Yeh hamara des-se hai,â€Â meaning “He is from my country.â€

The country he refers to is the subregion around Haryana, Punjab, or Western UP; or Marathwada, Konkan, or Telengana. By simply referring to his buddy as his fellow desi, the employee tells his boss in one simple 2-syllable word that he vouches for his buddy’s workmanship, loyalty and skills.

Living ten thousand miles away from India, in the US we at once identify ourselves with other people from different parts of India we see in our neighborhood and workplaces. Our children do the same at school because they as a group see a common set of challenges — both at home and at school — in assimilating into the American mainstream, which they know only they can understand. It is another story that in India and sometimes, even here in these United States, the Tamils, Telugus, Kannadigas; and the Marathis, Gujaratis, Sindhis, Punjabis, Haryanvis; and the Bengalis, Biharis, Oriyas and Assamese cannot stand each other. Â

How do we refer to ourselves when we are talking among ourselves? Indians? That is not esoteric enough, for, every outsider understands the term. Besides, it is the name given by Europeans.  So, no. Besides, a large number of us carry US passports. Many are green card holders, with one foot here and one foot in India, calling themselves Ghat-ka-kutta in their moments of confusion.

PIOs or People of Indian-origin? NRIs or Non-Resident Indians? or CIO, or Citizens of Indian Origin? These are long and clumsy bureaucratese.

In this context, Desi is just perfect, succinct, and rooted in India etymologically. And in the geographical context, it is expansive and inclusive, and includes Pakistanis, Bangladeshsis, Nepalese, and Sri Lankans as well. So, Desi, Amar Raho! or Long Live Desi.

Of course, the anglicized middleclass brown sahebs in India, being mental slaves of the British, will wait for the Oxford Dictionary to accept it into the English vocabulary before using the term themselves.

Spelling Bees: A Script Chauvinist’s Musings

Posted by admin in April 2011 on April 12, 2011

Â

Spelling Bees: A Script Chauvinist’s Musings

By Deepak Kotwal, Squirrel Hill, PA

The 2011 Spelling Bee is coming up in June. You have no doubt read last year, with some pride, that an Indian-American child won the Spelling Bee for the third year in a row, and also in eight out of the last twelve annual finals. Many of the mainstream publications marveled at this feat since Indian-Americans constitute less than 1% of US population. The children’s parents, who grew up in India, had no idea what a spelling bee was while they were growing up!

After all, if your mother tongue is any Indian language, there is no need for a spelling bee. It all has to do with the well thought-out and sci-entific nature the Devanagari script (देवनागरी लऱपि). The Latin script used for the English language is a simplistic Phoneme script in which each symbol represents a consonant or a vowel. There are only 26 of the-se. The rules of pronunciation are not uniform; For example, ‘book’ (बà¥à¤•à¥) has a short ‘u’ sound, whereas ‘boot’ (बूट) has a long ‘u’ sound.

The ancient rishis of India took a scientific approach while designing the Sanskrit alphabets, which is an Abugida system, in which consonants and vowels are combined together to represent a sound. They came up with 38 consonants and 14 vowels, which, when combine, represent 532 different sounds. The consonants were also grouped according to the part of the mouth used to vocalize these, as in pa, pha, ba, bha, ma, or ि फ ब ठम, which are ‘labial’ sounds or ओषà¥à¤ à¥à¤¯. Then there are dental, palatal and guttural etc. sounds.

Anyone who learnt to read and write any Indian language first, and, started learning English later, knows how hard and illogical English is. I consider myself very lucky that I did not learn English as my first lan-guage. Many of the first generation Indian-Americans studied only in an English medium school in India, as that was deemed to be the ticket to a better economic future.

Realizing the limitations of the Roman script, early Western scholars developed and adopted a standard method of using Latin letters with dia-critical marks to write Sanskrit and Devanagari (Ref: IAST ISO 15919 adopted in 1894 in Geneva at the International Congress of Orientalists

Have you noticed that although all Bollywood movies are in Hindi, the posters are invariably in English? Is this an expression of Indians’ slavish attitude towards all things English? Has Thomas Ba-bington Macaulay1 been thoroughly vindicated? Look for an article on Macaulay in the next issue.

Or, have the masses of India suddenly become literate in English?

The French colonialists forced Vietnam to abandon its native script. Thailand, on the other hand, which has never been colonized, proudly retains its own script today. Independent India appears to be abandoning its own scripts without any outside pressure! In my humble opinion, if Indian-American parents take the trouble of teaching their children to speak, read and write an Indian language and the Devanagari (or any other Indian) script, these children’s intellectual horizons and vision will be greatly expanded.