By Kollengode S Venkataraman thepatrika@aol.com

The details of the life of Bulleh Shah (or Syed Abdullah Shah Qadri), the 18th century Sufi poet of the Punjab region in the Indian subcontinent are not precisely known. Scholars believe, he was born in Bahawalpur in 1680 and died in Kasur in 1757, places in the Pakistani Punjab today.

In Bulla’s time, the Punjab region was in social, cultural, and political turmoil, with Aurangazeb (1658-1707) in Delhi and with armed raids from the west by Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah Abdali (1747–1773). The Sikhs, suffering the most from the brutality of the Mughals and from violent incursions from their western borders, were asserting themselves. Even within Islam, there was strife for control among the different factions.

Growing up and living in this era, Bulleh Shah, as we see in his poems in his mother tongue Punjabi, was disillusioned with the religious bloodletting even within Islam.

I heard one of his verses two years sometime back on YouTube (www.youtube.com/watch?v=gY41LNcSTiM). My Punjabi is zero, yet I could catch the first two lines. Having read earlier Bulleh Shah’s ideas on the Godhead, I could guess where he was leading to.

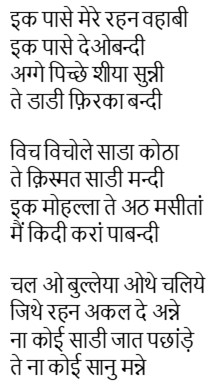

So, I asked Juginder Luthra, familiar to the Patrika readers, to get the verse in the Devanagari script and also to translate the verse into English.Mr. Suhendra Singh Ajmani, through Shri Sucha Singh, the Granthi Sahib at the Monroeville Gurudwara, got the Punjabi poem in the Gurumukhi script. Here is Bulleh Shah’s poem in translation dripping in disillusionment, sarcasm, ridicule, and anger, all rolled into one:

On my one side live Wahabis,

On the other, Deobandis;

In front Shias and behind, Sunnis,

All live in strict schism restrictions

In the midst of this is our house.

What bad luck!

One village — eight mosques!

Which one should I follow?

Get up Bulleya! Move to a place,

Where live those with blind mind,

Where no one recognizes my caste,

Where none has to agree with me!

Here is the original in the Gurumukhi and the Devanagari scripts:

..

Kabir Das (15th century) similarly shows his disgust on the polemics between Hindus and Muslims of his time.

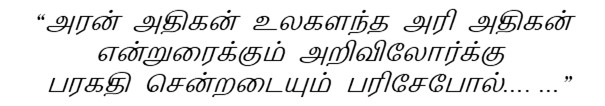

Rebelling against religious exclusivity has a long history in the Indian subcontinent, as we can see in the Bhakti literature all over the subcontinent. Here is a nuanced example in Tamil, from Kamba Ramayanam (10th or 12th century work), by the great Tamil poet Kambar:

Background: Hanuman is on his way to Sri Lanka to know the whereabouts of Sita. On his way, he has to cross over the Arundhati Hill Range with its peaks protruding into the skies like the palisades. Hanuman’s advisor, knowing that the mountain is dangerous to cross over, advises him to go around the hills. To describe the difficulty of crossing over the mountains, Kambar uses an unusual imagery:

Translation: This hill range is as difficult to fly over “as it is difficult for those ignoramus people to get moksha (liberation from bondage), who bicker on who is superior — Shiva or Vishnu.â€

What made Kambar to use such an unusual imagery? I can only surmise: in Kambar’s time (several centuries before Bulleh Shah), the followers of Shiva and Vishnu in the Tamil country were bickering between themselves in diatribes that must have disgusted Kambar. So, Kambar weaves a contextual imagery to subtly let people know how he feels on the futility of such tirades.

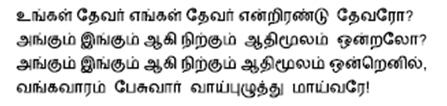

So, the expressions and imageries portrayed in these rebellious poems are always contextual for the place, time, and situation. Here is another example by the 14th century(?) Sivavakkiyar, which holds true for all times, all faiths, all places and all situations:

Your God and our God — Really two are there?

Is not the Primordial One here, there, and everywhere?

When the Primordial One is here, there, and everywhere,

Let them rot and perish, those who differentiate!

This type of theological squabbling is the bane among believers both of different faiths, but also within any one faith all over the world, including Christendom. The long history of the splintering in Christendom is gory since it was also tied to temporal and political power. In early centuries, Catholics (from Rome) and the Eastern Traditions (Greek, Russian, Serbian, and Syrian orthodox churches) were the main groups. But in the 16th century, the Church of England and the Lutherans in Germany broke away from Rome for different reasons. These Protestants later splintered into a large number of subgroups — Anglicans, Evangelicals, Mennonites, Charismatics, Fundamentalists, Baptists, Seventh Day Adventists, Methodists, Pentecostals… with constant bickering.

Consider this: Monroeville (population 28,000) in the eastern suburb of Pittsburgh, has 24 churches belonging to different Christian denominations and three Hindu temples. Imagine what Bulleh Shah would say if he were to visit Monroeville today!

But nowhere in the world, it seems to me, did the free spirits on spiritual matters have as much freedom to express themselves uninhibitedly as they had, and still have, in India. I say this because these types of unorthodox poems are recited and elaborated even today in Gurudwaras, Hindu temples, in kirtans, and in discourses all over India.

This is something the Occidental minds — both native Europeans and the Europeanized Indians — often fail to grasp. This is because, many of them, particularly the Europeanized Indians, have no grounding or familiarity with India’s many languages and its long spiritual journey and its many literary traditions. END