By Kollengode S Venkataraman

Tiru-mangai-alvaar, a Bhakti Tamil poet, is one of the twelve savants in the Vaishnava tradition in the Tamil country. He composed several hundred verses (part of the compendium called Divya Prabandham containing nearly 4000 verses) addressing Vaishnava deities in his pilgrimage. Analogously, the works of several Tamil Saiva poets (between the 6th and 9th centuries) called Tevaram and Tiruvachagam, and others are over 8000 verses in different meters.

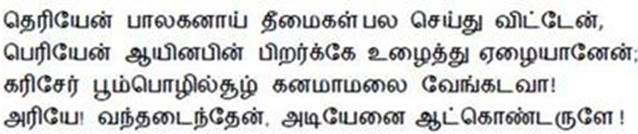

Literary critics date Tiru-mangai-alvaar between the 7th and 9th centuries. In one of his verses* he candidly pours out his personal inadequacies that resonate even today in our “modern†times. Here is his verse addressed to Venkateswara of Tirupati in India:

Here is the free-style non-poetical translation of the verse:

Unknowingly, in my youth, I indulged in countless bad deeds!

As an adult, laboring for others, I became impoverished!

O, Hari, the Lord of the Venkata Hills with surrounding forests

where elephants roam,

Here I am! Accept me [with all my faults] and grant me your grace!

We work in our jobs as employees, professionals, or as entrepreneurs and accumulate wealth of various kinds. But the poet here poignantly confesses that he was impoverished working for others. Is this not strange? We may never know who he worked for or the nature of his earnings over 1200 years ago. It is entirely possible that he, like us today, was not content with his earnings. Greed is so simple: no matter how much we earn and accumulate, often, we wish for more. But not getting more than what we actually get does not make us impoverished. So, why does the Alvaar confess, “I became ‘impoverished’ laboring for others?â€

The Alvar’s impoverishment probably was not material. Most likely, his was the spiritual impoverishment he suffered in earning his living — like the excessive servitude he showed to his employer. Or committing acts he should not have, or deliberately omitting acts he should have carried out, and making all kinds of unethical compromises along the way. In today’s parlance, it is like indulging in unethical practices to get ahead of others — even outright cheating and lying. Or by our becoming silent accomplices in the unethical business practices in work places, even in temples.

Such frustrations as in the confession above have been the bane of human existence. Here is another example: Pattinattaar, a Saiva mendicant in the 10th century Tamil Country, expresses the humiliation people endure when they go to rich and powerful people seeking favors. Incidentally, Pattinattaar was not born to poverty. He was a prosperous trader. He became a mendicant out of choice. A dramatic transformation occurred in his life when he realized, “Not even an ‘eye-less needle’ is of any help during our final exit.â€Â Here is his original expression in Tamil

![]() Sewing needles are of value and use only so long as they have the “eye.†Once the “eye†of the needle breaks off, the eye-less needle has no value whatsoever. Realizing this, Pattinattaar walked away from his wealth, becoming a wandering mendicant. He composed priceless poems on the human predicament in various situations using humor, cynicism, anger, irony or sarcasm in his expressions. People memorize these rhyming, alliterating verses even today.

Sewing needles are of value and use only so long as they have the “eye.†Once the “eye†of the needle breaks off, the eye-less needle has no value whatsoever. Realizing this, Pattinattaar walked away from his wealth, becoming a wandering mendicant. He composed priceless poems on the human predicament in various situations using humor, cynicism, anger, irony or sarcasm in his expressions. People memorize these rhyming, alliterating verses even today.

In one verse Pattinattaar puts his frustrations pretty bluntly in an alliterative and rhyming verse addressed to Shiva in Mount Kailasa:

Translation:

O, my father, the Lord of Mount Kailasa, when will be the dayÂ

when I don’t have to go behind the rich, whining about my problemsÂ

seeking favors by ingratiating myself with them and fawning over them?

And when will I be free from this misery, and experienceÂ

the bliss of being content with myself in solitude?

On the human yearnings for a higher call, every Indian language is a treasure trove of verses like the ones presented here. I say this with my sketchy understanding of Hindi/Bhojpuri/Awadhi Bhajans, Kannada Devaranamas and Vachanas, and after listening to pravachans on the shabads from the Adi Granth at the Gurudwara.

Unfortunately, in today’s India with the overemphasis on the anglicized education by rote, regional languages (including one’s own mother tongue) are losing their influence on youngsters. And nobody knows how to stem this tide. And there is only minuscule interest among India’s youngsters in one region to learn another Indian language. What is even worse is people’s benign condescension or outright hatred for other regional languages. This is a great Indian tragedy unfolding in front of the whole nation that nobody seems to recognize — or care, even when they recognize it. ♣

* I acknowledge Kalyani Raghavan of Edwewood, PA for the exact reference to this verse.  ♣