By Kollengode S. Venkataraman (October 2007)

Geographically, India forced out the British and the Europeans starting on August 14, 1947. But the Indian polyglot media, with its elite angrezi media in the lead, continue to give great importance to West’s recognition of India this and India that. And even after sixty long years, Indian elite still craves for recognition from its erstwhile colonial masters, who were actually, its occupiers. It never occurs to India’s “elite” why it took so long for the West to recognize India’s inherent strengths. That is another story. Now is the time to emphasize the positive.

For forty year after independence, India suffered through the Nehruvian controlled economy, which in mid-1980s took India to the brink of bankruptcy. With no other option, the Congress Party was forced to loosen its stranglehold on the economy. Since then, India’s foreign exchange reserves have been steadily growing. Now it is in excess of $200 billion. China’s is 1200 billion. Without embarrassment, the Congress Party shamelessly takes credit for this liberalization.

Without the need for any statistics, even cursory visitors to India these days see the strengths not only of India’s macroeconomy, but also feel and experience the vibrancy of ordinary unpad (illiterate) Indians. The Wall Street Journal and others routinely feature articles on the strengths of India’s English-speaking manpower that is “cheap” by the standards of the industrialized West. India’s huge population now is an opportunity, not a problem. My, my, how perceptions change!

Now, multinationals, big and small, driven primarily by the cost advantage, invest heavily in India in manufacturing and in R&D in pharmaceuticals, transportation, and biotechnology. With the cost of healthcare rapidly escalating in the West, many in the West are looking at the option of going to Asia (India, Thailand, and others) for elective surgeries. It costs a lot less in India, including travel, hospital fees, and sightseeing.

That all these changes came in India just in the last 20 years is quite impressive in itself. What is more impressive is that these changes are mostly the result of the instinctive enterprise of native Indians. All that the government did was loosen its stranglehold (derisively called the Permit-Licence-Quota Raj of the Congress Party) on the economy, which enormously benefited only India’s established businesses, bureaucracy and politicians, at the cost of everybody else.

Overseas visitors to India — mostly tourists and business people — complain about the terrible state of the physical infrastructure like roads, rails, electric power, communications, and mass transit. If you talk to Indian sociologists, social workers and activists, or read newspapers such as The New York Times, Washington Post, Le Monde, Spiegel, and others, you see a different India with a widening chasm between the educated Indians who gained by globalization and the others left behind.

You can see this for yourself in India. See the quality of primary education your nephews/nieces or your siblings’ grandchildren get. And then go to a primary school in a nearby rural area, and see the difference between the two schools. See if the poorer kids even have footwear; see if they sit on benches in classrooms or squat on dirt floors in the open; or talk to people in Ekal Vidyalaya (www.ekalvidyalaya.org) or others who run schools in rural India for the poor.

Then go to any hospital where middle class Indians go for treatment — I am not talking about the top-of-the-line Apollo/Escort hospitals where India’s rich and other patients from outside India go for treatment. And then go to a nearby public hospital where the poor go. See the difference.

This is not peculiar to India. The much-touted trickle-down theory of Reagan-era did not work. The US is now more socioeconomically polarized than it was 30 years ago. But the starkness in the differences you see in India quite unsettling. This has led to deep fissures among the India’s social segments because the beneficiaries of globalization are the 300-million strong educated class that is anglicized to varying degrees. Large numbers (over 400 million by one count) are left behind.

The following scenes encapsulate India’s irony, paradox, dilemma:

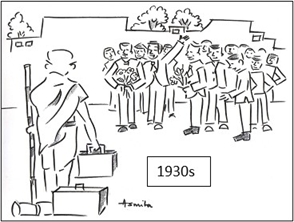

The Father of India, Mohandas Gandhi, the London-educated

barrister, on his return from South Africa in the 1930s gave up his 3-piece suite and arrived in Bombay in the traditional Gujarati dhoti and turban. A large number of Indians, including London-educated barristers in their flannel jackets and ties in the warm, humid Bombay, were there at the sea port to enthusiastically receive Gandhi.

And a few years after Independence, in 1953, the very first Filmfare awards ceremony was held at Metro Cinema in Bombay, and the post-awards dinner was at the Willingdon Club run by India’s brown sahebs. Bimal Roy, who had won two awards for Do Bigha Zamin was denied entry into the club because Roy was in his white Bengali dhoti.

Now come to May, 2007, sixty years after India’s independence. Source for this story is in Kumudam, the most popular Tamil weekly.

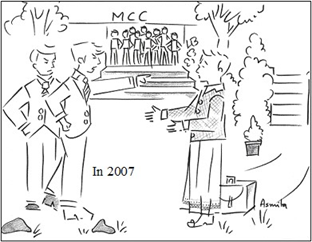

Place: the so-called Traditional Chennai. Venue: The Madras Cricket Club. A group of Rotary Clubs was holding a seminar on how to make the benefits of the IT boom in India reach rural India in the club auditorium .

A US-returned Chennai native, Mr. A. Narayanan, a senior honorary official in India’s federal ministry of Panchayat Raj (or ministry for Grassroots Democracy), was an invited speaker because of his expertise in the field. He had returned to India after living in the US for several years. Since he was going to speak on improving rural India’s development, Narayanan went to the Madras Cricket Club in a dhoti, worn in the traditional Madras-style. As it happened to Bimal Roy in Bombay, Narayanan too was denied admission to the club in the “tradition-bound” Chennai. Mind you, the club was only the venue, and not the organizer of the event.

And this happened 60 years after India’s Independence! And there was not even a whimper in Chennai’s English media for A. Narayanan being denied entry into the Madras Cricket Club because of his dhoti.

Looking at the irony, one can say during its colonial days, India’s leaders might have been politically slaves, but were free in Spirit. And with spiritual strength, they drove the European colonial occupiers out with very little bloodshed. The Partition was a bloody scar though.

But, today, India’s ruling and social elite is spiritually a slave of the West, while remaining nominally free politically and economically. Where India will be in the next twenty years depends very much on how well India reconciles its accelerated growth in the aggregate with the imperatives for more equitable opportunity for all to benefit, the inequities are no more exclusively along caste lines. In the years ahead, the voices of India’s conscience keepers will only become louder. The challenge for India is for it to regain its spiritual freedom, using the word “spiritual” in its transcendental sense. — END