By Kollengode S Venkataraman (Published in July 2007)

This is a new feature we are starting, and this can sustain only with your participation. Indian literature is studded with nuggets and gems on ethics, faith, personal conduct, charity, justice and human foibles. Since these ideas evolved well before the time of the papyrus, Indian thinkers composed them in condensed verses so that people can easily commit them memory. These poet-philosophers wrote these verses frugally choosing words paying attention to meter, rhythm, alliterations, and rhymes and other rules unique to the grammar of the languages. Hundreds of verses — four, eight, twelve, and sixteen lines — chiseled with great brevity are available in all languages.

We welcome readers to share with others on an ongoing basis verses in your language (Kannada, Telugu, Marathi, Malayalam, Urdu, Bengali, Hindi, Punjabi, Sindhi, Oriya, Assamese, Konkani… … Briefly comment on the verse—who wrote it and when, literal meaning, literary nuances and beauty, and the import—so that others unfamiliar with the language can share your pleasure. Include the verse in the original script for publishing as part of the story. Call Prema or Venkataraman (724 327 0953) before you start for the nonbinding guidelines. Asmita Ranganathan would provide illustrations, her time and our space permitting, to reinfornce the story.

Several centuries ago, a king in India commissioned a Sthapati (traditional temple architect well versed in its art) to build a temple to commemorate a big event in his reign.

The architect went to the neighboring hill known for its excellent quality granites and selected blocks of the black stone for the work — pillars, steps, dwajastham-bham (flag post), and of course, the vig-raham (stone-carved images) for the presiding deity in the sannidhi (shrine).

He spent several days looking for the good granites. Putting all his knowledge to use, the temple architect selected the blocks of stones for his work and hauled them to the temple site. Obviously, selecting the granite for carving the deity was most demanding—the boulder should give a metallic sound on being tapped with his chisel.

He carefully split the best granite block into two halves. With one half he carved an exquisite image that was consecrated in the sanctum.

He used the other half for a step that takes worshippers to the sanctum. Only by climbing on this step, people could reach and enter the sanctum. With constant use of priests and devotees walking in and out, the surface of the granite step became smooth.

Sivavakkiyar was a Saivite Tamil ascetic. Literary scholars believe his

time was 14th century or earlier. It is possible, Sivavakkiyar is the name given to him after his time by his admirers, who collectively called the compendium of his works Siva-vakkiyam (literally, the Words of Shiva). Shiva-vakkiyar can mean the person who spoke the words of Shiva.

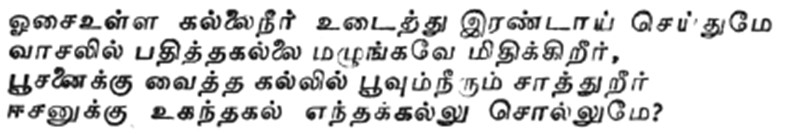

Sivavakkiyar uses the vivid imagery in the above scene that many have seen in temples, churches, mosques, and other monuments all over the world, and raises a thoughtful question in a four-line verse:

Translation:

Selecting a metal-sounding* granite, you split it into two.

And a step you made with one block. See, it has become smooth with your use!

Out of the other block, you carved an image for worship, offering the image holy water and flowers.

Why don’t you tell me, sir? Which one of the two is dearer to God?

* Metal-sounding granites are traditionally preferred for carving images.

If you think Sivavakkiyar is castigating only Hindus, you are

entirely missing the point. The message is to all organized religions. Sivavakkiyar, out of compassion to his fellow-citizens, teasingly asks all of us to ponder over when we imprison ourselves in rigid dogma, theological absolutes, and empty rituals, making them ends in themselves. In reality though, dogma, theology, and rituals are not ends in themselves, but only necessary steps in our spiritual journey as Seekers of Truth.

We can go one-step further. All human organizations—political parties, corporate boardrooms, governments, sports teams, and even religious organizations—deify their stars and heroes. And as they deify and fawn over stars, people knowingly and unknowingly step on those who are the very foundations of the organizations making the organizations work.

Even in our personal efforts to succeed, we step on others. Often, we don’t even think what happens to those on whose back we rode to success, till we see somebody else riding on us to get ahead.

After succeeding in life, many realize that they paid a terrible price, often intangible, for what they thought was “success.†One of the Tamil Bhakti poets puts it well: “I was impoverished by my servitude to others.†The poverty he talks about is the poverty of the Spirit in the midst of material prosperity.  — END