By Kollengode S. Venkataraman, ThePatrika@aol.com

The New York Times’ editorial bias against the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is well known. Its editorials and editorial Board’s consensus articles have been anti-Modi. Modi-bashing writers bearing Indian names from universities, think tanks, and other literary figures — such as Amartya Sen, Salman Rushdie, Pankaj Misha and Arundhati Roy — are a staple in the Times’ Op-ed page articles. In 2013, before the last general elections in 2015 the Nobel-winning economist, the Bharat Ratna recipient, and Harvard professor Amartya Sen said, he does not want Modi to become India’s prime minister as he does not have secular credentials.

Op-ed pages are supposed to accommodate a diversity of opinions. But on India’s social, cultural and political issues, not only are the NYT editorials are consistently anti-Modi (which is entirely acceptable), but even its news coverage and visuals that go with the stories are also anti-Modi, and OpEd writers appear to be chosen to echo its editorials. For all the freedom of expression the Times professes, often, on India-related articles, it shuts off readers’ comments knowing full well the type of response it would receive from a wide swathe of Indian-American readers.

In this background, the Times published this article (May 20, 2019) by Jeffrey Gettleman with the title without recognizing the irony: The Choice in India: “Our Trump” or a Messier Democracy, (www.nytimes.com/2019/05/20/world/asia/modi-india-election.html)

In the article, Gettleman writes: “These days, it’s not unusual to hear Indians describe Modi as ‘our Trump,’ which is said in antipodal ways, either with pride or scorn.” He should have identified the names and affiliations of those who claim Modi as “Our Trump.”

Gettleman quotes “a well-known political commentator” telling him this on Modi: “Trump and Modi are twins separated by continents.” His article only mentions the name of “the well-known political commentator” without identifying his affiliation. He is Chandra Bhan Prasad. This is unusual for the Times, which rarely uses the names of people without identifying their affiliations. A Google-search revealed that Mr. Prasad is associated with the Center for the Advanced Study on India (CASI) at the University of Pennsylvania, This is how the CASI describes Prasad in its website www.casi.sas.upenn.edu/visiting/prasad :

“Chandra Bhan Prasad is widely regarded as the most important Dalit thinker and political commentator in India today, advocating on behalf of the more than sixteen percent of India’s population who have historically been regarded as untouchable by orthodox Hinduism. Mr. Prasad is a research affiliate on CASI’s Dalit research program and serves as a key advisor to the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI). He was the first Dalit to gain a regular space in a nationally circulating Indian newspaper, more than fifty years after India’s independence, quickly attracting national attention and widespread readership … … His articles and books are used by South Asia faculty in universities throughout the world to question longstanding assumptions about caste and Indian society. Prasad studied at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, where he completed his M.A. and M.Phil. His story and writings can be seen at his website: www.chandrabhanprasad.com.“

We acknowledge Mr. Prasad is a commentator with an impressive pedigree. Nevertheless, he is a partisan, representing and fighting for the Dalits’ causes on a global platform. His erudition and rise from humble background are exemplary, and we respect him for his commitment to his causes.

In India, and in all democracies including the U.S., appeasement vote-bank politics are widely practiced by political parties based on a whole range of local criteria. In India, appeasement politics is successfully exploited by a plethora of pressure groups based on religion, caste, ethnicity and locally relevant minority status. India’s Dalit leaders have been effectively using the vote-bank politics with a rare blend of finesse and muscle power to advance their causes. Good for them. As a Dalit activist and political commentator, Mr. Prasad is free and fully entitled to work for his causes and air his opinion on anyone, anytime, anywhere.

But it is deceitful and disingenuous on Gettleman’s and the Times’ part not to identify Prasad’ affiliation and background. How often do we see the NYT using names in stories without identifying their affiliations?

Now, with this information on Mr Prasad as a Dalit activist on a global platform, and the Dalit leaders’ visceral dislike for Modi, when you read Mr. Prasad’s comment that “Trump and Modi are twins separated by continents,” you get a better understanding and a different feeling. Incidentally, Modi belongs to India’s Backward Caste.

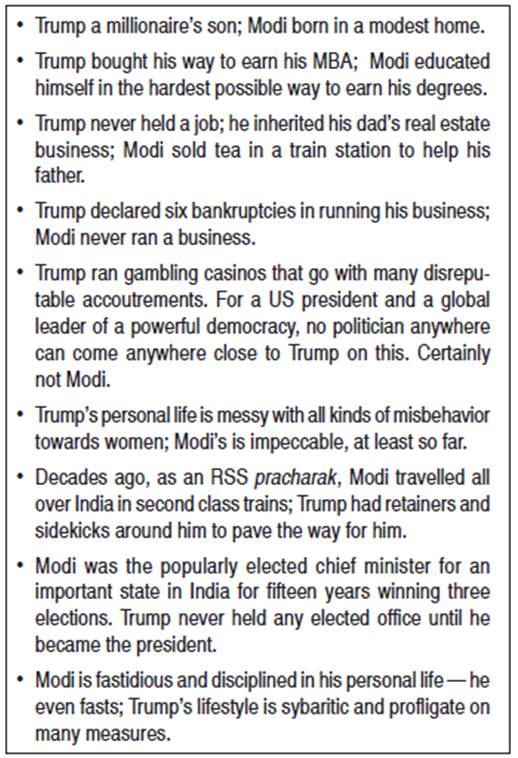

Contary to Mr. Prasad’s characterization that Modi and Trump are “twins separated by continents,” Modi and Trump stand in sharp contrast to each other on a whole range of criteria. See the box below.

These contrasts aside, Gettleman goes on: “Political analysts say [pray, who are they?] there is no shortage of similarities between the two, including their combative style, their prolific use of Twitter and their talent for stoking nationalism ‘and spreading fear,’ to firm up their bases.”

Show me one politician who does not have a combative style. And if one is not combative, why should one even seek elective office? Combative styles are natural to rulers. There is even a Sanksrit term for it, Rajasic temperament (literally, temperament of the rajas, or kings), in today’s context, the temperament of people wielding raw power, such as elected officials, senior bureaucrats, corporate CEOs and senior managers.

Which politician is not nationalistic? Politicians all over the world — including US Presidents — have used fear to firm up their bases. In our own time, U.S. presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Reagan, Bush-43 and Trump effectively used fear to firm up their base. Bush-43 even went to a costly war in Iraq inciting fear of a nuclear Iraq — a blatantly untrue premise.

Today, with social media and instant communication, nobody has a monopoly over data, analysis, interpretations and opinions, in political and social studies involving races, castes, ethnicities and religions. This includes those sitting in the ivory towers of tenured jobs in endowed chairs in universities, or those spending retirement years in think tanks.

Many of these intellectuals (this is fast becoming a pejorative term these days) — both from the right and left — sit far away from the fields of action, in urban centers, in touch with “like-minded†thinkers living in different time zones, different countries, and different cultures. Predictably, people who interact only with other “like-minded†people end up in echo chambers in different topics, impervious to differing ideas and hypotheses to consider.

Even in the sterile physical and biological sciences, it is painful for someone who has built up his/her whole career on axioms and ideas, to discard them in the face of mounting evidence against them. It is that much more difficult in societal and political studies dealing with class, race, ethnicity, poverty and wealth — and in the Indian context, also involving languages, castes, and religions.

Governing India is a task unlike anything that one can comprehend, given how complex and diverse India is on every criterion known to mankind. India is not like a well-cultivated California vineyard or a Florida orchard. It is like a dynamic tropical forest’s complex ecosystem that supports and sustains countless species of plants, birds, reptiles and animals in perpetual struggle to maintain a semblance of equilibrium.

Trying to understand other cultures through sterile reports, comparison tables, graphs and pie charts, not to speak of GDPs and GDP growth rates, per-capita-this and per-capita-that, though necessary, is just not sufficient. The global English media, particularly in the US and UK, working on deadlines and time- and space-constraints, do not seem to get it.

The Indian English media’s brown sahebs do not care about what the media in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia say on India. These brown sahebs’ current obsession with the US media is understandable. Today, the U.S. is militarily powerful, economically rich and dynamic, technologically innovative, and globally influential on many fronts. And nearly 3 million Indians and Indian-Americans live in the US, most of them in professional jobs. And among them are the Brown Saheb Indians’ classmates, cousins, nephews and nieces, sons and daughters.

But their fascination with the UK is puzzling. It is just a holdover from India’s colonial past. Britain is no more “Great” Britain. And the empire collapsed over 70 years ago, and India became a republic 70 years ago.

In assessing the Indian elections in 2019 the English-speaking West (mainly, US and UK), and their surrogates in the anglicized Indian English media completely missed what was happening on the ground. No wonder they could not recognize the subterranean rumblings.

In a famous Buddhist parable, ten blind men of Hindustan tried to describe an elephant through their tactile experience on the part they touched. Today, the media moguls of Englishtan, blinded by overconfidence and condescension, sitting in New York, London, and Washington, and their deputies in India’s English media houses pass judgement on India based on their partial understanding and fixated opinions. They are partially correct; but they missed the big picture, as it happened in this elections.

Of these two groups, members of the anglicized Indian media are the worst. One can understand the historical biases and prejudices of the western media, like the Times, Time, and the London broadsheets. But the Indian brown sahebs’ unfamiliarity of the Indian hinterland is inexcusable. These Indian brown sahebs are essentially products of upper crust or upper middle-class India, living in Mumbai, Delhi and other metro areas. Most of them are educated in only-English-medium schools from KG onwards, and may have a working familiarity with — vernaculars like Hindi, Punjabi, Marathi, Tamil, Malayalam — And many are further educated in England and the U.S., cut off from India’s ethos on many measures.

With the 2019 elections results going haywire from their predicted outcome, they are in disarray and look foolish. Having gone to “Convent” schools, they are in a confessional mode now.

One hopes now that these brown sahebs will liberate themselves from the Lutyen mindset of looking at Indian through American and British lenses; and as Rajiv Malhotra of the Infinity Foundation has said on many occasions, learn to understand India through Indian lenses. This will not be easy, and will take time, This would involve some serious unlearning and re-learning of their ideas of the Indian subcontinent in all its complexities, warts and all. As any addict knows, freeing oneself from bad habits or recursive thinking, is difficult. This would involve several topics in which they need to learn simultaneously:

1. Learning India’s history through the several regional dynasties going beyond the Mauryas, Guptas, Lodhis, Khiljis, and the Mughals. For example, learning about Satavahanas, Solankis, Kakatiyas, Cholas, Pandyas, Cheras, Marathas, Vijayanagara Empire, and the Sikhs;

2. Familiarizing themselves with Indian’s complex histories in all its social, cultural, linguistic and literary transitions;

3. Learning one or two regional languages, not as ‘vernaculars,’ but in some depth to understand their histories, literary works and the social, ethical, and philosophical ideas they convey;

4. Learning to appreciate India’s pre-Mughal architectural wonders by understanding the civil and structural engineering basis of the temples that have stood for several hundred years before the arrival of Islam, and which are still standing with minimal maintenance;

5. Understanding the basis of India’s unique place in visual arts (sculpting, metal casting, and paintings), and pre-Mughal performing arts (music and dance).

If they do this in some seriousness, they would get a better insight into their own history and ethos in the years ahead. Otherwise, they will become irrelevant in their own time. And what is worse for them, they will become a laughingstock for the rest of India, which they have already become at least in one measure, as the results of the 2019 elections show. ♠