By V Krishnaswami, Ross Twp., PA

e-mail: vkrishnaswami@comcast.net

Editor: V. Krishnaswami, a longtime resident in our Metro area, grew up in Tamil Nadu. Sanskrit was his second language in high school, and also at the Loyola College, Chennai. He was taught Sanskrit at home by both his grandfather, an erudite scholar in the language, and his father, who was well versed in both Sanskrit and Classic Tamil. Both were lawyers. Krishnaswami’s interest included Kavyas (poetry), scriptures, stotras (hymns)… He has read Sanskrit dramas in the original — the works of Bhasa, Kalidasa, Dandi and Bhabhuti. His interest in Appayya and Nilakantha Dikshita started when his grandfather taught him Nilakantha Dikshita’s Shanti-vilasam. He feels that Sankara’s Brahmasutra Bhashya is a masterpiece in literature, logic and hermeneutics (the subject dealing with the theory and methodology of interpretation wisdom literature, and philosophical texts).

Krishnaswami came to Pittsburgh in 1973 as a fellow in cardiology at the then Presbyterian University Hospital. He practiced cardiology in Pittsburgh at Mercy and UPMC between 1988 and 2017. He was a clinical professor at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Medicine. Now retired, he was involved in teaching and research all through his career.

Sanskrit is the mother of Indic subbranch Indo-European languages. ‘Samskritam’ literally means a language of perfection. The beauty of this “language of the Gods†was elucidated by William Jones(Chief Justice of Supreme Court in Bengal at the time of Warren Hastings) in his address to Asiatic society on February 2, 1786: “Sanskrit language …is of a wonderful nature, more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin more exquisitely refined than either.â€

If you poll the people in India where Sanskrit as a language is well known even if not spoken or understood, about Sanskrit poets, I will be surprised if they can name anybody beyond Kalidasa. Some may have heard of Dandi, Magha, may be even Bavabhooti. Sanskrit poesy appears dead after the time of these masters. But hat is not true.Â

It was prevalent in religious works of Sankara and his disciples in 8th century, Ramanuja (9th/10th century) and later, Madhva in 11th century. Many people wrongly think there was no Sanskrit poetry after 12th century. even though it was not flourishing. Tulasidas Goswami (16th century). Muthuswami Deekshitar (18th century) are great Sanskrit Bhakti poets.

Nuilakantha Dikshita was a Sanskrit poet, born in South India in 16th century. He was born in the illustrious family of Appayya Dikshita. We know that he was born at the end of 15th century and lived to about middle of 16th century. Neelakanta was a genius, great poet, philosopher and a distinguished statesman. He was the chief administrator during the rule of Thirumala Nayaka, ruler of Madurai, a splintered state after the collapse of the Vijayanagar empire.

Impressed by the young Nilakantha’s exposition of the text Devimahatmyam, the King Tirumalai Nayak was so impressed that he offered him a position as an administrator in his kingdom. His exquisite poetical works go beyond Bhakti, and are known for their humor, suggestion, sarcasm, Slesha (double entendre) — all in measured quantity.

His works include plays (his magnum opus being Nalacharitra Nataka) epic poems like Siva-leela-arnavam and Gangavataranam. His minor works include Kalividambanam, Sabaranjana Satakam, Santivilasam  reflecting the hypocrisy in the society in Kaliyuga among various professions. Some of his works are not extant and some only partially available.

Neelakanta Dikshta’s poetry is like honey in a bottle. The pleasure starts right with the look, easy to obtain and sweet, unlike the works of some great poets. For example, Bhavabhuti whose works are heavenly, are like cool coconut water in summer, but you have to get the fibers out and break the shell before you enjoy it. Dikshita’s style is simple, his words are fluent and spontaneous coming from the heart (Sahrudaya), with not much of grammar problems. His descriptions of nature in Gangavataranam is splendid. He also wrote heart-melting Bakthi poetry in which in spite of all his scholarly understanding of the Upanishads, he makes a case that one can attain liberation only by totally surrendering to God and through His Grace — Her in his case, since he was a bakta of Goddess Meenakshi, the presiding deity of Madurai temple) — and not by Gnana (knowledge) alone, somewhat akin to Martin Luther’s idea of Grace.

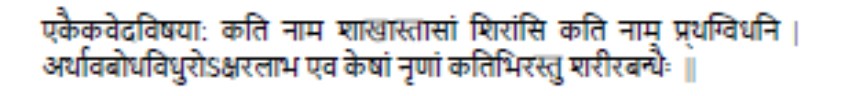

Here is a sloka from Anandasagaratavam a beautiful work in prayer to Goddess Meenakshi of Madurai:

Translation:

How many different recensions (Shakha) there are in the Vedas!

How many different Upanishads in each of these recensions!

How many births will be needed for mere rote learning of these texts — Not to speak of the study to understand their meaning!

In this profound verse the poet rhetorically says, any amount of knowledge acquired by the study of Vedic or other religious texts alone without God realization (for which you need God’s Grace) will not bring hope for liberation in this life.

Editor: We will share with readers other examples of Neelakanta Dikshita’s poetry in the ongoing issues. Â

Home: