By Kollengode SÂ Venkataraman

e-mail: Â ThePatrika@aol.com

Taayumaanavar, a great poet-spiritualist-philosopher (1705-1742), lived in Tamil Nadu, expounding Advaita Saiva Siddhantam. His Tamil name splits into Taayum and aanavar, meaning in Tamil He Who is Also the Mother, a descriptive reference to Shiva. In Sanskrit, it would be Maatr-bhooteshwara.

He was born not in a brahmin family but in a Vellala family deeply steeped in Saivism. His parents were Kediliappa Pillai and Gajavalli Amma. Though most of his poems are addressed to Saiva deities, he was a universalist on matters of spirituality. In many verses he addresses the Infinite using a Tamil word PoruL, literally meaning “The Thing.†Most probably, he would have struggled for a long time and failed to find a word or phrase to comprehensively and precisely define the Infinite. So, he chose poruL, the same way the Upanishads use tat, literally meaning That.

Etymologically speaking, the English that is cognate with, and derived from, the Sanskrit tat. Can you get any closer either phonetically or in spelling?

In an alliterating Tamil verse Taayumaanavar says how difficult it is to master one’s own mind, a prerequisite in our spiritual journey:

You can control an elephant, catch hold of a tiger’s tail,

Grab the snake and dance, dictate to angels,

Transmigrate into another body, walk on water or sit on the ocean;

But it is far more difficult to still your mind and remain quiet.

He was impatient with theological hair-splitting, common in his time, as it is in ours. After serving as a minister for the Maratha king Vijayaranga Chokkanatha Nayak of Tanjavoor, he quit and became a mendicant.

Taayumaanava Swamy was a scholar in both Tamil and Sanskrit. If you want to understand and enjoy his several hundred verses composed in a variety of complex Tamil meters, grounding in Sanskrit and the Indian metaphysical ideas are necessary. Well-versed in the two classical languages, he would have easily identified charlatans of his time as we see in the following non-poetic translation of his verse in a dasakam (padigam in Tamil), a set of ten verses on a theme, called Siddhar Ganam:

Coming to think of it, the illiterate are indeed virtuous.

Look at my karma and my intelligence [that’s impetuous].

I’m well-read, but still live in ignorance!

If a wise person advises, “The liberating Jnana (wisdom) is worthy of pursuit,â€

Karma (action) is more important, I will assert.

But if one defends Karma as the better option,

I’ll argue, “The good old Jnana is more important.â€

With a Sanskrit pandit, I will elaborate on how great Tamil is.

When meeting people well-versed in Tamil,

I will dazzle them with a few Sanskrit shlokas.

My conceited bombast frustrates everyone, but convinces none!

O, the skilled Siddhas, You’ve reconciled the ideas of Vedanta and Siddhanta!

Will this talent of mine ever give me Mukti (liberation)?

The answer to his rhetorical question is obvious: No. Taayumaanavar deftly brings out the hypocrisy in us by employing the first person singular in the verse. Obviously, he is not referring to himself. But when you read his verse, you may see shades of yourself in the first person pronouns I, my, mine, and first-person case-endings in the verbs. This technique is commonly used by Bhakti poets all over India since the 5th century to temper our vanity and pride.

Today we see modern versions of Taayumaanavar’s archetype all over India. You have to only replace Sanskrit with English, French, German, Arabic, Persian, or any Indian language other than your native tongue.

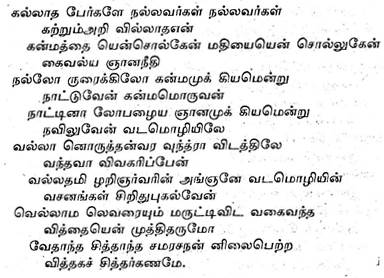

Here is the Tamil original for you to enjoy the alliterative and rhyming verse of this great poet-philosopher:

♦