By Kollengode S. Venkataraman (July 2013)

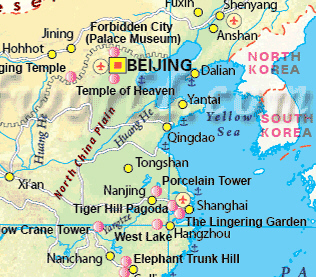

This past March I was in China on work spending nearly a month in one place. It was not Beijing or Shanghai. I was in Huangdau, a third tier city, in the extended metropolitan region around Qingdao, a beautiful second tier city along the Yellow Sea. See the map.

The enviable economy of China with 10% growth year after year and lifestyles of those who benefited in the growth are well known. But the growth came with a price. In cities the skyline is often covered with smog. The evening sun looks like the full moon, and folks walk with masks over their face.

The Chinese government in the Mao Zedong era, alarmed at the rapid increase in population, enforced the draconian one-child-per-family policy. This contained the population growth. But as predicted, this policy led to married couples born in that era now in their 40s and 50s and both

working, having to take care of four elders – his and her parents. With longevity guaranteed because of genetics, lifestyle and eating habits, this poses serious social and economic problems in China where family ties and obligations are taken seriously.

\With the equivalent of Medicare and Social Security practically absent, the responsibility for elderly care in terms of money, time, and resources are on the single-son and single-daughter of the seniors. People powerful enough in the party, or who became rich enough in the economic boom, have the resources to meet their obligations. But middle-income families are under strain. Government is re-thinking its one-child-one-couple policy, partly because of the predicted shortage of work force down the road.

The one-child-one-family policy ensured the reduction and even reversal in population growth, but this did not address the Chinese preference for boys over girls. Nature unaided by technology for gender selection has kept the gender ratio over a narrow range, with around 105 boys for every 100 girls.

But with the marvels of modern technology for detecting the gender of fetuses—amniocentesis, ultrasound and digital imaging techniques—many married couples in China, both educated and not-so-educated, opt for terminating pregnancies if the child conceived is a girl. This gender selection has skewed the gender ratio. Now they have 120 boys for every 100 girls nationally. In pockets the gender ratio is skewed badly with 150 boys for 100 girls. The situation is identical in India, where they have 112 boys for 100 girls. However, in pockets of Punjab, Gujarat, Rajasthan, UP, and Bihar, far more boys are there for 100 girls.

Mara Hvistendahl in recent her book Unnatural Selection notes that the skewed gender ratio makes societies more prone to violence. “[T]he dearth of women along the frontier in the American West probably had a lot to do with its [the West] being wild. In 1870, the sex ratio west of the Mississippi was 125 men to 100 women. In California it was 166 to 100. In Nevada it was 320. In western Kansas, it was 768.”

The skewed gender ratio in China has led to an unintended consequence based on supply and demand.

I was waiting for my colleagues in the Crown Plaza Hotel in  downtown Qingdao. It was chilly, windy and raining. I was standing outside the lobby and seeing—and hearing—a loud music band attired in bright red costume playing traditional music with cymbals and Chinese drums. A black Mercedes with flower decorations pulled in. The music became louder with Chinese dragon dancers joining in the merriment. The bride in Western bridal costume came out. With her was a man in his mid-thirties, He was balding with a receding hairline.

downtown Qingdao. It was chilly, windy and raining. I was standing outside the lobby and seeing—and hearing—a loud music band attired in bright red costume playing traditional music with cymbals and Chinese drums. A black Mercedes with flower decorations pulled in. The music became louder with Chinese dragon dancers joining in the merriment. The bride in Western bridal costume came out. With her was a man in his mid-thirties, He was balding with a receding hairline.

Chinese believe if it rains on the day of wedding, the wife will dominate  over her husband. My colleagues arrived to take me for lunch. Seeing the rain, they mockingly felt sorry for the groom. The wedding milieu was a good topic during lunch. I asked innocently, “Is the man in dark suit with the bride her uncle or elder brother bringing her to the wedding place?”

over her husband. My colleagues arrived to take me for lunch. Seeing the rain, they mockingly felt sorry for the groom. The wedding milieu was a good topic during lunch. I asked innocently, “Is the man in dark suit with the bride her uncle or elder brother bringing her to the wedding place?”

Surprised at my question, pat came the reply from one of my colleagues, “No. He is the groom!”

“Hmm. He looked old,” I said, “He is getting bald and he has receding hair. Don’t Chinese men get married in their mid twenties?”

This led to a lengthy discussion on the marriage scene among the professionals in today’s China.

As in other parts of the world, tradition runs deep in China. The Chinese Communist Party, trying for decades after the revolution, has ceased to erase traditions on life transitions such as marriage.

In China, it is traditional that the groom pays “bride money” to the bride in person with crisp currency notes. Checks and demand drafts are not accepted—they are against the tradition. Even fifteen years ago, the bride money was manageable—a few thousand renminbis (RMBs), the Chinese currency. $1= 6.3 RMB. The bride has to be satisfied that the man can support her.

Decades ago, the man took his new wife her into the home of his parents to live after wedding. Now things have become expensive, with classy expectations. China’s explosive prosperity is one reason. Another factor is the skewed man-made gender ratio. With a smaller pool of women available for a larger pool of men seeking partners, women are picky.

The typical monthly starting salary for a professional (accountant, lawyer, engineer, physician) in Huangdao is around 60,000 RMBs/year. Now, the bride money for professionals has increased several fold—100,000 RMBs or even more. This is almost twice the starting gross salary.

In addition, the brides, who are in short supply, also expect the grooms to have an apartment to move into after the wedding. And apartments are VERY expensive. A 100-sq.meter (1000 sq. ft), 3-BR apartment in Qingdao in a “desirable” neighborhood costs 800,000 to 1 million RMBs. The down payment is 20%, or 200,000 RMBs.

So, young Chinese professional men need 300,000 RMBs, just to get married, with their starting salary around 60,000 RMBs/year. And the expenses on the wedding day are also on the groom’s family. With normal cars (cost: 80,000 RMBs) — Jaguars are over 600,000 RMBs — becoming a necessity, young men are stressed out.

So, Chinese couples, after having their much-desired boy, not only start to save for his schooling/college, but also for helping their only adult son 25 years down the road with the bride money and apartment.

That explained why the groom at the Crown Plaza Hotel was in his mid-thirties with a receding hairline and was bald. He has been saving money for years for sure. And he was also spending time wooing picky Chinese women to consider him good enough to be their mate.

But this situation is not a panacea for Chinese young women. Even though they demand an apartment before marriage, the apartments are often registered only in the groom’s name. After all, his parents have financed it. But her assets are jointly owned.

But Chinese women today in general, and professional educated women in particular—much like young educated women everywhere—have become picky, sometime too picky for their own good. This is the same as what we see here in the US. Even after the success of the Feminist Movement and the economic security that comes with education, Ivy League women prefer to marry other Ivy Leaguers, and professional women choose other professional men as mates.

My colleagues also told me Chinese men are wary about professional women who come across too aggressive and ambitious. And for single professional women over 32 or 33, the pool of eligible, compatible, unmarried professional men is small and there are not too many to go around. It is a balancing act in the wooing game for the Chinese young men and women. It is quite stressful. The really rich men deploy paid agencies to screen potential candidates. Others depend on parents, relatives and friends to meet women.

If this is the situation for professionals in China, we can only imagine the challenges of the millions of the working poor in China.

The economic impact of this trend is huge. By one estimate, nearly 25% of their 8% annualized GDP growth, or 2%, is because of the demand for new housing and cars among working professionals. This demand sustains basic industries such as steel, cement, home appliances, tiles, bathroom fixtures, construction jobs, home decorations…

With far more men than women in the productive and reproductive age group in China, in the years to come, the married life of Chinese will be dominated by their wives, even if it does not rain on their wedding day.

===========================